Bradycardia is a resting HR < 60 bpm and may be physiological (e.g. in athletes or during sleep), due to intrinsic conduction disease (e.g. heart block), or due to external influences (e.g. cholinergic or adrenergic-blocking medications). With an intrinsic conduction disease, the problem can occur at any point in the SA-AV-His-Purkinje pathway.

PR INTERVAL

The normal PR interval is 120–210 milliseconds (some books say 200 ms!). PR interval is measured from the start of the P wave to the start of the ventricular complex, whether that is a Q or an R wave. At a standard paper speed of 25 mm/s, each small square is equivalent to 40 ms. The normal PR interval is therefore 3–5 (ish) small squares

CAUSES

–> An SA node disease may result in inappropriate sinus bradycardia and pauses either due to failure of the SA node to depolarise or failure of the SA node to capture the surrounding atrial myocardium (sino-atrial exit block).

–> Disease at the level of the AV node will result in alteration in the PR interval or P-QRS relationship. This is often referred to as heart block (HB), of which there are three common types:

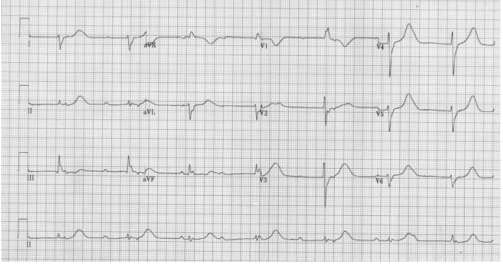

1st degree: Each P-wave is followed by a QRS complex, but the PR interval is prolonged (> 200 ms).

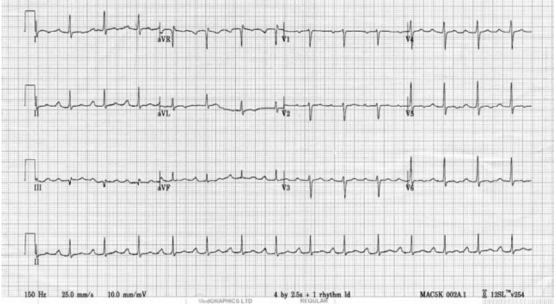

2nd degree: Not all P waves are followed by a QRS complex.

Mobitz Type I: In Mobitz type I (Wenckebach) there is a progressive prolongation of the PR interval (AV conduction) until eventually an atrial impulse is completely blocked. When an atrial impulse is completely blocked there will be a P wave without a QRS complex. This pattern is often referred to as a “dropped beat.”. Here each depolarization results in the prolongation of the refractory period of the atrioventricular node (AVN); hence itis progressive. Eventually, an impulse comes when the AV node is in its absolute refractory period and will not be conducted. This will manifest on the ECG as a P wave that is not followed by a QRS complex. This non-conducted impulse allows time for the AV node to reset, and the cycle continues. When seen in young, fit people with high vagal tone, often nocturnally, it may be benign. However, in the elderly it can be a sign of significant AV node disease and there may be a risk of inducing higher degrees of AV block, particularly with AV nodal blocking agents (e.g. beta-blockers, verapamil, diltiazem, amiodarone).

Mobitz Type II: In Mobitz type II there is a constant PR interval across the rhythm strip both before and after the non-conducted atrial beat. Each P wave is associated with a QRS complex until there is one atrial conduction or P wave that is not followed by a QRS.

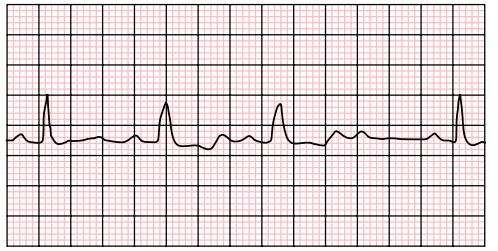

3rd degree : There is complete dissociation of P-waves and QRS complexes due to complete block at the AV node (complete HB). The QRS rate is slower than the P-wave rate as the ventricular complexes are generated by an escape rhythm within the ventricular conduction system, which has a lower intrinsic automaticity rate compared to atrial tissue. If the escape rhythm originates high within the His-Purkinje system, the escape rhythm may consist of narrow QRS complexes (since onward ventricular depolarisation occurs via the normal conduction pathway) and only slightly reduced HR (40–50 bpm). The lower the escape rhythm in the His-Purkinje system, the broader and

slower the QRS complexes and the higher the risk of progressing to asystole

MANAGEMENT

–> For bradycardia, in a symptomatic patient give atropine 500 µg IV, and if the patient remains symptomatic, repeat this dose every 3–5 minutes up to a maximum of 3 g. If there has been a calcium antagonist or beta-blocker overdose consider using glucagon. If the patient is at risk of developing asystole, transvenous pacing may be required. Risk factors for a bradycardia deteriorating to asystole include a recent episode of asystole, Mobitz type II AV block, third-degree (complete) heart block or ventricular standstill of more than three seconds.

–> Complete heart block with narrow complexes may not require immediate pacing, as AV junctional ectopic pacemakers can provide a reasonable and stable cardiac output.

–> Transvenous pacing is the definitive treatment, but if the expertise is not readily available, patients may be managed temporarily with either transcutaneous pacing or an epinephrine infusion in the range of 2–10 µg per minute.

–> If there is no pacing equipment immediately available, fist pacing may be attempted. Apply serial rhythmic blows with a closed fist over the left sternal edge to pace the heart at physiological rate of 50–70 times a minute

INDICATIONS FOR TEMPORARY PACING IN THE PERIOPERATIVE PERIOD

- Complete heart block

- Second degree heart block

- First degree heart block with left bundle branch block

- Trifascicular block

OTHER INDICATIONS FOR TEMPORARY PACEMAKER

- Bradycardia unresponsive to atropine

- Inferior wall MI which can impair perfusion to AV node

- Anterior wall MI affecting bundle branches in the IVS

- Overdrive pacing for AV reentry tachycardia and VT

- Post aortic or VSD or tricuspid surgery

- Asystole with p wave activity

FIRST DEGREE HEART BLOCK

SECOND DEGREE HEART BLOCK

COMPLETE HEART BLOCK