- Heat capacity: The heat energy required to raise the temperature of a given object by one degree. (J.K−1 or J.°C−1)

- Specific heat capacity: The heat energy required to raise the temperature of one kilogram of a substance by one degree. (J.kg−1.K−1 or J.kg−1.°C−1)

- But not all heat energy results in a temperature change.

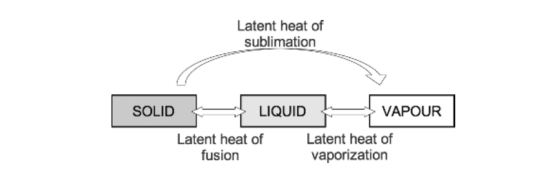

- Latent heat: This is the heat energy that is required for a material to undergo a change of phase. (J) The heat is not utilised for raising the temperature, but for changing the phase.

- If heat is applied to matter, temperature increases until the melting or boiling point is reached. At these points the addition of further heat energy is used to change the state of matter from solid to liquid and from liquid to gas. This does not cause a change in temperature. The energy required at these points is referred to as latent heat of fusion and latent heat of vaporisation, respectively.

- Specific latent heat is the heat required to convert one kilogram of a substance from one phase to another at a given temperature.

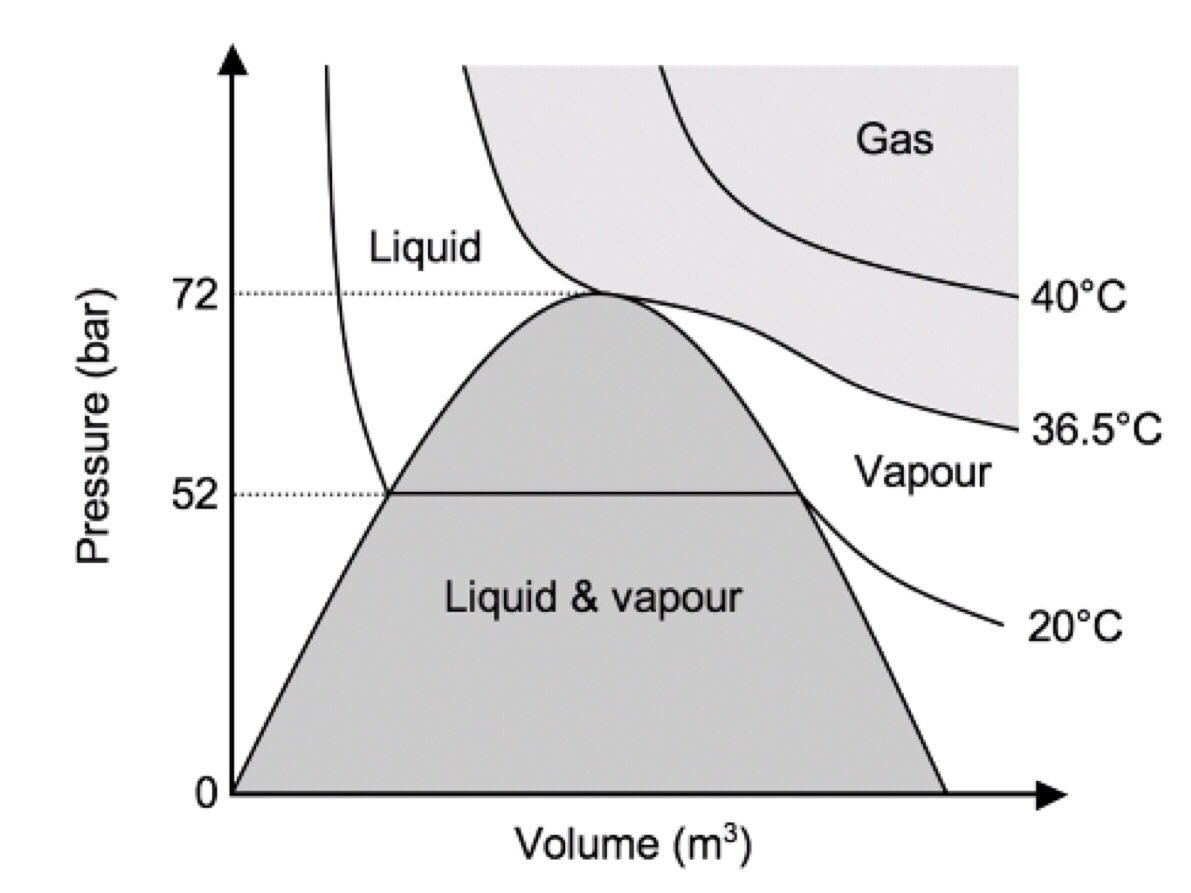

- As temperature increases, the amount of additional energy required to overcome the intermolecular forces of attraction falls until the critical temperature of a substance is reached. At this point the specific latent heat is zero, as no further energy is required to complete the change in state of the substance.

APPLICATIONS

- Variable bypass vaporisers function by passing a small amount of fresh gas through the vaporising chamber, which is fully saturated with anaesthetic vapour. This removes vapour from the chamber. Further vaporisation from the anaesthetic liquid must occur to replace the vapour removed, which requires energy from the latent heat of vaporisation. This cools the remaining liquid, reducing the saturated vapour pressure and thus the concentration of anaesthetic vapour delivered, resulting in an unreliable device.

- Temperature compensation features help to overcome this problem; a copper heat sink placed around the vaporising chamber is one such example. Copper has a high heat capacity and donates energy required for latent heat of vaporisation, maintaining a stable temperature and reliable delivery of anaesthetic agent.

- Evaporation of sweat is another example. It requires the latent heat of vaporisation, which is provided by the skin’s surface, exerting a cooling effect upon the body.

- Evaporation from open body cavities can be a cause of significant heat loss from patients while under anaesthesia.

- These principles are also applicable to blood transfusion. Blood is stored at 5°C and has a specific heat capacity of 3.5 kJ·kg−1·K−1. If cold blood were transfused into a patient without pre-warming, the heat energy required to warm the blood to body temperature would need to be supplied by the patient, which would have a significant cooling effect.