It’s beneficial to do a determination of nutrition risk (using scores like nutritional risk screening [NRS 2002], NUTRIC score etc ) on all patients admitted to the ICU for whom volitional intake is anticipated to be insufficient; it should also include an evaluation of comorbid conditions, function of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and risk of aspiration.

Energy requirements may be calculated either through simplistic formulas (25-30 kcal/kg/d), published predictive equations, or the use of indirect calorimetry. Predictive equations should be used with caution, as they provide a less accurate measure of energy requirements than indirect calorimetry in the individual patient. In the obese patient, the predictive equations are even more problematic without availability of indirect calorimetry. Calories provided via infusion of propofol should be considered when calculating the nutrition regimen.

Sufficient (high-dose) protein should be provided. Protein requirements are expected to be in the range of 1.2–2.0 g/kg actual body weight per day and may likely be even higher in burn or multitrauma patients

ENTERAL NUTRITION

Enteral Nutrition (EN) is the preferred route of feeding over Parenteral Nutrition (PN) for the critically ill patient who requires nutrition support therapy

Nutrition support therapy in the form of early EN be initiated within 24–48 hours

In the setting of hemodynamic compromise ( patients requiring significant hemodynamic support including high dose catecholamine agents, alone or in combination with large volume fluid or blood product resuscitation to maintain cellular perfusion), EN should be withheld until the patient is fully resuscitated and/or stable. Initiation/reinitiation of EN may be considered with caution in patients undergoing withdrawal of vasopressor support.

In the majority of MICU and SICU patient populations, while GI contractility factors should be evaluated when initiating EN, overt signs of contractility should not be required prior to initiation of EN. (Bowel sounds are only indicative of contractility and do not necessarily relate to mucosal integrity, barrier function, or absorptive capacity) The argument for initiating EN regardless of the extent of audible bowel sounds is based on studies (most of which involve critically ill surgical patients) reporting the feasibility and safety of EN within the initial 36–48 hours of admission to the ICU.)

In most critically ill patients, it is acceptable to initiate EN in the stomach.

Critically ill patients should be fed via an enteral access tube placed in the small bowel if at high risk for aspiration or after showing intolerance to gastric feeding.

If patients who are at low nutrition risk with normal baseline nutrition status and low disease severity (eg, NRS 2002 ≤3 or NUTRIC score ≤5) who cannot maintain volitional intake do not require specialized nutrition therapy over the first week of hospitalization in the ICU.

Full nutrition by EN is appropriate for patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) / acute lung injury (ALI) and those expected to have a duration of mechanical ventilation ≥72 hours, as these 2 strategies of feeding have similar patient outcomes over the first week of hospitalization.

Based on expert consensus, we suggest that patients who are at high nutrition risk (eg, NRS 2002 ≥5 or NUTRIC score ≥5, without interleukin 6) or severely malnourished should be advanced toward goal as quickly as tolerated over 24–48 hours while monitoring for refeeding syndrome. Efforts to provide >80% of estimated or calculated goal energy and protein within 48–72 hours should be made to achieve the clinical benefit of EN over the first week of hospitalization.

Patients should be monitored for tolerance of EN (determined by patient’s complaints of pain and/ or distention, physical exam, passage of flatus and stool, abdominal radiographs). Inappropriate cessation of EN should be avoided. Holding EN for gastric residual volumes <500 mL in the absence of other signs of intolerance should be avoided. The time period that a patient is made nil per os (NPO) prior to, during, and immediately following the time of diagnostic tests or procedures should be minimized to prevent inadequate delivery of nutrients and prolonged periods of ileus. Ileus may be propagated by NPO status

The guidelines suggest that GRVs not be used as part of routine care to monitor ICU patients receiving EN. Instead alternative strategies may be used to monitor critically ill patients receiving EN: e.g. careful daily physical examinations, review of abdominal radiologic films, and evaluation of clinical risk factors for aspiration. For those ICUs reluctant to stop using GRVs, care should be taken in their interpretation. GRVs in the range of 200–500 mL should raise concern and lead to the implementation of measures to reduce risk of aspiration, but automatic cessation of EN should not occur for GRVs <500 mL in the absence of other signs of intolerance.

It recommends that enteral feeding protocols be designed and implemented to increase the overall percentage of goal calories provided. The use of a volume-based feeding protocol or a top-down multistrategy protocol to be considered.

Patients placed on EN should be assessed for risk of aspiration. Steps to reduce risk of aspiration should be employed. The following measures have been shown to reduce risk of aspiration:

# In all intubated ICU patients receiving EN, the head of the bed should be elevated 30°-45°.

# Agents to promote motility such as prokinetic drugs (metoclopramide and erythromycin) or narcotic antagonists (naloxone and alvimopan) should be initiated where clinically feasible.

# Use of chlorhexidine mouthwash twice a day should be considered to reduce risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia.

# It recommends for diverting the level of feeding by postpyloric enteral access device placement in patients deemed to be at high risk for aspiration

# For high-risk patients or those shown to be intolerant to bolus gastric EN, delivery of EN should be switched to continuous infusion.

It recommends using a standard polymeric formula when initiating EN in the ICU setting and to avoid the routine use of all specialty formulas in critically ill patients in a MICU and disease-specific formulas in the SICU.

Diarrhea in the ICU patient receiving EN should prompt an investigation for excessive intake of hyperosmolar medications, such as sorbitol, use of broad spectrum antibiotics, Clostridium difficile pseudomembranous colitis, or other infectious etiologies. Most episodes of nosocomial diarrhea are mild and self-limiting. EN should not be automatically interrupted for diarrhea but feeds should be continued while evaluating the etiology of diarrhea in an ICU patient to determine appropriate treatment.

Immune-modulating enteral formulations (arginine with other agents, including eicosapentaenoic acid [EPA], docosahexaenoic acid [DHA], glutamine, and nucleic acid) should not be used routinely in the MICU. Consideration for these formulations should be reserved for patients with TBI and peri operative patients in the SICU.

“We cannot make a recommendation at this time regarding the routine use of an enteral formulation characterized by an anti-inflammatory lipid profile (eg, omega-3 FOs, borage oil) and antioxidants in patients with ARDS and severe ALI, given conflicting data.”

Commercial mixed fiber formula not be used routinely in the adult critically ill patient prophylactically to promote bowel regularity or prevent diarrhea. Consider the use of a commercial mixed fiber-containing formulation if there is evidence of persistent diarrhea. Avoid both soluble and insoluble fiber in patients at high risk for bowel ischemia or severe dysmotility. Consider the use of small peptide formulations in the patient with persistent diarrhea, with suspected malabsorption or lack of response to fiber.

It recommends the use of a fermentable soluble fiber additive (eg, fructo- oligossaccharides [FOSs], inulin) for routine use in all hemodynamically stable MICU/SICU patients placed on a standard enteral formulation. 10–20 g of a fermentable soluble fiber supplement be given in divided doses over 24 hours as adjunctive therapy if there is evidence of diarrhea.

While the use of studied probiotics species and strains appear to be safe in general ICU patients, they should be used only for select medical and surgical patient populations for which RCTs have documented safety and outcome benefit. Guidelines doesn’t make a recommendation for the routine use of probiotics across the general population of ICU patients.

Antioxidant vitamins (including vitamins E and ascorbic acid) and trace minerals (including selenium, zinc, and copper) may improve patient outcome, especially in burns, trauma, and critical illness requiring mechanical ventilation . Renal function should be considered when supplementing vitamins and trace elements.

Enteral glutamine not be added to an EN regimen routinely in critically ill patients. While enteral glutamine exerts a trophic effect in maintaining gut integrity, its failure to generate a sufficient systemic antioxidant effect may partially explain the lack of outcome benefit.

PARENTERAL NUTRITION

In the patient at low nutrition risk (eg, NRS 2002 ≤3 or NUTRIC score ≤5), exclusive PN be withheld over the first 7 days following ICU admission if the patient cannot maintain volitional intake and if early EN is not feasible.

In the patient determined to be at high nutrition risk (eg, NRS 2002 ≥5 or NUTRIC score ≥5) or severely malnourished, when EN is not feasible, we should initiate exclusive PN as soon as possible following ICU admission.

In patients at either low or high nutrition risk, use of supplemental PN be considered after 7–10 days if unable to meet >60% of energy and protein requirements by the enteral route alone. Initiating supplemental PN prior to this 7-10 day period in the patient already receiving EN does not improve outcome and may be detrimental to the patient.

It suggests the use of hypocaloric PN dosing (≤20 kcal/ kg/d or 80% of estimated energy needs) with adequate protein (≥1.2 g protein/kg/d) in appropriate patients (high risk or severely malnourished) requiring PN, initially over the first week of hospitalization in the ICU.

It suggests withholding or limiting traditional soyabean oil based IV fat emulsions (IVFEs) during the first week following initiation of PN in the critically ill patient to a maximum of 100 g/wk (often divided into 2 doses/wk) if there is concern for essential fatty acid deficiency.

The use of alternative IVFEs (SMOF [soybean oil, MCT, olive oil, and fish oil emulsion], MCT, OO, and FO) may provide outcome benefit over soy-based IVFEs; and so their use can be considered in the critically ill patient who is an appropriate candidate for PN.

Use of standardized commercially available PN versus compounded PN admixtures in the ICU patient has no advantage in terms of clinical outcomes.

Parenteral glutamine supplementation not be used routinely in the critical care setting.

A target blood glucose range of 140 or 150–180 mg/dL should be considered for the general ICU population

In patients stabilized on PN, periodically repeated efforts should be made to initiate EN. As tolerance to EN improves, the amount of PN energy should be reduced and finally discontinued when the patient is receiving >60% of target energy requirements from EN.

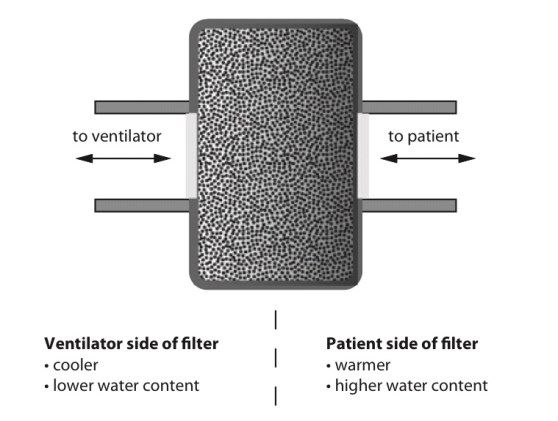

Specialty high-fat/low-carbohydrate formulations designed to manipulate the respiratory quotient and reduce CO 2 production not be used in ICU patients with acute respiratory failure

Fluid restricted energy-dense EN formulations (1.5-2.0 kcal/mL) be considered for patients with acute respiratory failure

Serum phosphate levels should be monitored closely and replaced appropriately when needed.

ICU patients with acute renal failure (ARF) or AKI be placed on a standard enteral formulation and that standard ICU recommendations for protein (1.2–2 g/kg actual body weight per day) and energy (25–30 kcal/kg/d) provision should be followed. If significant electrolyte abnormalities develop, a specialty formulation designed for renal failure (with appropriate electrolyte profile) may be considered.

There is an approximate amino acid loss of 10-15 g/d during CRRT. Patients receiving frequent hemodialysis or CRRT receive increased protein, up to a maximum of 2.5 g/kg/d. Protein should not be restricted in patients with renal insufficiency as a means to avoid or delay initiating dialysis therapy.

EN be used preferentially when providing nutrition therapy in ICU patients with acute and/or chronic liver disease. Nutrition regimens should avoid restricting protein in patients with liver failure. A dry weight or usual weight be used instead of actual weight in predictive equations to determine energy and protein in patients with cirrhosis and hepatic failure, due to complications of ascites, intravascular volume depletion, edema, portal hypertension, and hypoalbuminemia. Nutrition regimens should avoid restricting protein in patients with liver failure, using the same recommendations as for other critically ill patients

Standard enteral formulations be used in ICU patients with acute and chronic liver disease. There is no evidence of further benefit of branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) formulations on coma grade in the ICU patient with encephalopathy who is already receiving first-line therapy with luminal-acting antibiotics and lactulose.

PANCREATITIS

The initial nutrition assessment in acute pancreatitis should evaluate disease severity to direct nutrition therapy. As disease severity may change quickly, we should do frequent reassessment of feeding tolerance and need for specialized nutrition therapy.

Patients with mild acute pancreatitis, don’t require specialised nutrition therapy ; instead they should be advanced to an oral diet as tolerated. If an unexpected complication develops or there is failure to advance to oral diet within 7 days, then specialized nutrition therapy should be considered.

Patients with moderate to severe acute pancreatitis should have a naso-/oroenteric tube placed and EN started at a trophic rate and advanced to goal as fluid volume resuscitation is completed (within 24–48 hours of admission)

Patients with mild to moderate acute pancreatitis do not require nutrition support therapy (unless an unexpected complication develops or there is failure to advance to oral diet within 7 days).

A standard polymeric formula should be used to initiate EN in the patient with severe acute pancreatitis. Although promising, the data are currently insufficient to recommend placing a patient with severe acute pancreatitis on an immune-enhancing formulation at this time.

Use of EN over PN is recommended in patients with severe acute pancreatitis who require nutrition therapy.

Use of probiotics be considered in patients with severe acute pancreatitis who are receiving early EN.

Tolerance to EN in patients with severe acute pancreatitis may be enhanced by the following measures:

>Minimizing the period of ileus after admission by early initiation of EN.

>Displacing the level of infusion of EN more distally in the GI tract. Changing the content of the EN delivered from intact protein to small peptides, and long-chain fatty acids to medium-chain triglycerides or a nearly fat-free elemental formulation.

>Switching from bolus to continuous infusion

For the patient with severe acute pancreatitis, when EN is not feasible, use of PN should be considered after 1 week from the onset of the pancreatitis episode.

TRAUMA

Immune-modulating formulations containing arginine and FO be considered in patients with severe trauma.

The use of either arginine-containing immune-modulating formulations or EPA/DHA supplement with standard enteral formula is suggested in patients with TBI.

OPEN ABDOMEN

Provide an additional 15–30 g of protein per liter of exudate lost for patients with Open Abdomen

POSTOPERATIVE MAJOR SURGERY

Determination of nutrition risk (eg, NRS 2002 or NUTRIC score) be performed on all postoperative patients in the ICU but traditional visceral protein levels (serum albumin, prealbumin, and transferrin concentrations) should not be used as markers of nutrition status.

EN be provided when feasible in the postoperative period within 24 hours of surgery, as it results in better outcomes than use of PN or STD

The routine use of an immune-modulating formula (containing both arginine and fish oils) in the SICU for the postoperative patient who requires EN therapy, is recommended

The guidelines recommend enteral feeding for many patients in difficult postoperative situations such as prolonged ileus, intestinal anastomosis, OA, and need of vasopressors for hemodynamic support.

Evidence suggests that early EN makes anastomoses stronger with greater collagen and fibrin deposition and fibroblast infiltration has been shown in a meta-analysis, with no worsening effect on anastomotic dehiscence

For the patient who has undergone major upper GI surgery and EN is not feasible, PN should be initiated (only if the duration of therapy is anticipated to be ≥7 days). Unless the patient is at high nutrition risk, PN should not be started in the immediate postoperative period but should be delayed for 5–7 days.

Upon advancing the diet postoperatively, patients be allowed solid food as tolerated and that clear liquids are not required as the first meal.

BURNS

🍪 A very early initiation of EN (if possible, within 4–6 hours of injury) is suggested in a patient with burn injury. Patients with burn injury should receive protein in the range of 1.5–2 g/kg/d.

🍪 A very early initiation of EN (if possible, within 4–6 hours of injury) is suggested in a patient with burn injury. Patients with burn injury should receive protein in the range of 1.5–2 g/kg/d.

SEPSIS

Do not use exclusive PN or supplemental PN in conjunction with EN early in the acute phase of severe sepsis or septic shock, regardless of patients’ degree of nutrition risk.

It suggests the provision of trophic feeding (defined as 10–20 kcal/h or up to 500 kcal/d) for the initial phase of sepsis, advancing as tolerated after 24–48 hours to >80% of target energy goal over the first week and a delivery of 1.2–2 g protein/kg/d.

CHRONICALLY CRITICALLY ILL

Chronically critically ill patients (defined as those with persistent organ dysfunction requiring ICU LOS >21 days) be managed with aggressive high-protein EN therapy and, when feasible, that a resistance exercise program be used.

OBESE

Nutrition assessment of the obese ICU patient should also focus on biomarkers of metabolic syndrome, an evaluation of comorbidities, and a determination of level of inflammation, in addition to those parameters described for all ICU patients.

Efforts to provide >50%-65% of goal calories should be made in order to achieve the clinical benefit of EN over the first week of hospitalization.

High-protein hypocaloric feeding be implemented in the care of obese ICU patients to preserve lean body mass, mobilize adipose stores, and minimize the metabolic complications of overfeeding.

For all classes of obesity, the goal of the EN regimen should not exceed 65%–70% of target energy requirements as measured by indirect calorimetry (IC). If IC is unavailable, use the weight-based equation 11–14 kcal/kg actual body weight per day for patients with BMI in the range of 30–50 and 22–25 kcal/kg ideal body weight per day for patients with BMI >50. Protein should be provided in a range from 2.0 g/kg ideal body weight per day for patients with BMI of 30–40 up to 2.5 g/kg ideal body weight per day for patients with BMI ≥40.

If available, an enteral formula with low caloric density and a reduced NPC:N (non-protein calorie:nitrogen ratio) be used in the adult obese ICU patient.

Additional monitoring to assess worsening of hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, hypercapnia, fluid overload, and hepatic fat accumulation is needed in the obese critically ill patient receiving EN.

The obese ICU patient with a history of bariatric surgery should receive supplemental thiamine prior to initiating dextrose-containing IV fluids or nutrition therapy. In addition, evaluation for and treatment of micronutrient deficiencies such as calcium, thiamin, vitamin B 12 , fat- soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K), and folate, along with the trace minerals iron, selenium, zinc, and copper

➖END OF LIFE SITUATIONS

➖END OF LIFE SITUATIONS ➖

➖

Specialized nutrition therapy is not obligatory in cases of futile care or end-of-life situations.

#nutrition , #EnteralNutrition , #ParenteralNutrition

Reference: Guidelines for the Provision and Assessment of Nutrition Support Therapy in the Adult Critically Ill Patient: Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (1) Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition Volume 40 Number 2 February 2016 159–211 (2) Volume 33 Number 3 May/June 2009 277-316 , 2009 American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition and Society of Critical Care Medicine