-

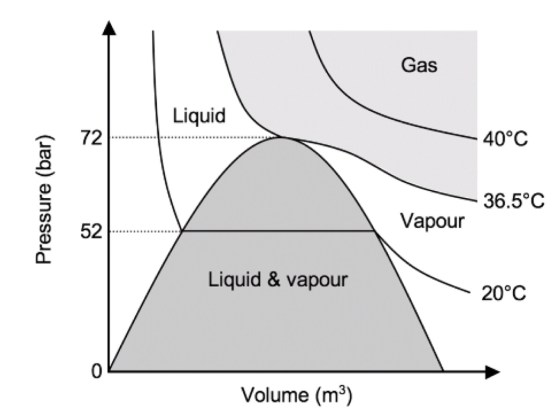

An isotherm is a line of constant temperature

-

Compressed gases in a cylinder can either stay as a gas, or change state to form a liquid due to the higher pressure (both carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide do this).

-

A graph of pressure against time for nitrous oxide is shown below. The isothermal lines are shown for 40°C, 36.6°C and 20°C.

-

At 40°C, nitrous oxide is above its critical temperature and so it is a gas no matter whatever pressure is being applied.

-

When it is compressed (moving from right to left along the isotherm) the pressure increases smoothly. At 36.6°C (the critical temperature), as soon as the pressure reaches the critical pressure (72 bar), the gas becomes a liquid.

-

At 20°C, once the pressure reaches 52 bar (the saturated vapour pressure of nitrous oxide at 20°C), some of the gas condenses so that liquid and vapour are both present. Further decreases in volume cause more vapour to condense, with no associated rise in pressure. When all the vapour has condensed to a liquid, any further reduction in volume causes a rapid rise in pressure.

-

In most circumstances, nitrous oxide is stored below its critical temperature of 36.4 C. It therefore exists in the cylinder as a vapour in equilibrium with the liquid below it.

-

To determine how much nitrous oxide remains in a given cylinder, it must be weighed, and the weight of the empty cylinder, known as the tare weight, subtracted. Using Avogadro’ s law, the number of moles of nitrous oxide may now be calculated. V/n= K, where V = volume of gas, n = amount of substance of the gas, K = a proportionality constant

-

Using the universal gas equation, the remaining volume can be calculated. PV = nRT, where P = pressure, V = volume, n = the number of moles of the gas, R = the universal gas constant (8.31 J/K/mol), T = temperature

CRITICAL TEMPERATURE AND PRESSURE

- Critical temperature: The temperature above which a gas cannot be liquefied regardless of the amount of pressure applied. (K/°C). At this point the specific latent heat is zero, as no further energy is required to complete the change in state of the substance.

- Critical pressure: The minimum pressure required to cause liquefaction of a gas at its critical temperature. (kPa/Bar)

- The latent heat of vaporisation is the heat energy required to change the state of a substance from liquid to vapour.

- At its critical temperature, a liquid will change spontaneously into vapour without heat being required. In other words, the latent heat of vapourisation is zero

GAS LAWS

- Boyle’s law

- At a constant temperature, the volume of a fixed amount of a perfect gas varies inversely with its pressure.

- PV = K or V ∝ 1/P . Also P 1 V 1 = P 2 V 2

- Ⓜ️NEMO> water Boyle’s at a constant temperature

- Example: P 1 V 1 relates to the pressure and volume in the cylinder and P 2 V 2 relates to the pressure and volume at atmospheric pressure. For example, oxygen is stored at 13 800 kPa (absolute pressure) in gas cylinders. If the internal volume of the cylinder is 10 litres, the volume this cylinder will provide at atmospheric pressure: 13 800 × 10 = 100 × V 2. So V 2 = 1380 litres. However, 10 litres will remain within the cylinder, so 1370 litres will be usable at atmospheric pressure.

- Charles’ law

- At a constant pressure, the volume of a fixed amount of a perfect gas varies in proportion to its absolute temperature.

- V/T = K or V ∝ T

- Ⓜ️NEMO> Prince Charles is under constant pressure to be king

- Gay–Lussac’s law (The third gas law)

- At a constant volume, the pressure of a fixed amount of a perfect gas varies in proportion to its absolute temperature.

- P/T = K or

- P∝T

- Perfect gas: A gas that completely obeys all three gas laws or A gas that contains molecules of infinitely small size, which, therefore, occupy no volume themselves, and which have no force of attraction between them.

- It is important to realize that this is a theoretical concept and no such gas actually exists. Hydrogen comes the closest to being a perfect gas as it has the lowest molecular weight. In practice, most commonly used anaesthetic gases obey the gas laws reasonably well.

- Other gas laws of relevance:

- Avogadro’s hypothesis: at a constant temperature and pressure, all gases of the same volume contain an equal number of molecules.

- Dalton’s law: the pressure exerted by a mixture of gases is the sum of the partial pressures of its constituents.

- Henry’s law: at a constant temperature, the amount of gas dissolved in a given volume of liquid is directly proportional to the partial pressure of that gas in equilibrium with the liquid.

- Henry’s law can be used to show that the amount of oxygen dissolved in blood is proportional to the partial pressure of oxygen in the alveolus. The amount of dissolved oxygen carried in blood is 0.023 ml·dl −1 ·kPa −1 . At atmospheric pressure, this accounts for a very small and insignificant fraction of oxygen delivery. However, under hyperbaric conditions, the dissolved fraction increases and becomes a more significant source of oxygen delivery to tissues

- At absolute zero, the theoretical volume of an ideal gas is zero. Real gases have liquefied before this point.

- Boyle’s, Charles’ and Gay-Lussac’s law are combined to form the ideal gas law.

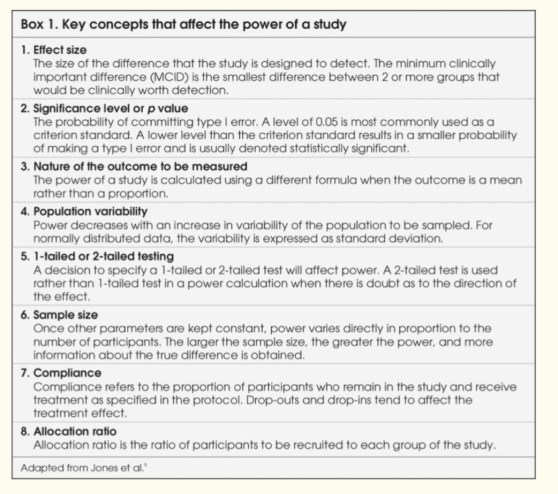

POWER OF A STUDY

🔸The power of a study is defined as “the ability of a study to detect an effect or association if one really exists in a wider population.”

🔸In clinical research, we conduct studies on a subset of the patient population because it is not possible to measure a characteristic in the entire population. Therefore, whenever a statistical inference is made from a sample, it is subject to some error.

🔸Investigators try to reduce systematic errors with an appropriate design so that only random errors remain. Possible random errors to be considered before making inferences about the population under study are type I and type II errors.

🔸To make a statistical inference, 2 hypotheses must be set: the null hypothesis (there is no difference) and alternate hypothesis (there is a difference).

🔸The probability of reaching a statistically significant result if in truth there is no difference or of rejecting the null hypothesis when it should have been accepted is denoted by type I error. It is similar to the false positive result of a clinical test.

🔸Type I errors are caused by uncontrolled confounding influences, and random variation. The probability of a type I error occurring can be pre-defined and is denoted as α or the significance level (represented by the p-value). The corresponding 1−α, or 95%, represents the specificity of the test.

🔸The p value may vary from 1 (the groups are the same) to 0 (100% certainty that the groups are different).

🔸In most clinical research, a conventional arbitrary value of P<0.05 is commonly used. This is an arbitrary figure which means that there is a 1 in 20 (5%) chance that there really is no difference between groups. Said in another way, if the null hypothesis is rejected, there should be a 5% chance of a type I error.

🔸As the p value becomes lower the possibility of there being ‘no difference when one has been found’ becomes more and more remote (e.g. p = 0.01, 1 in 100 and p = 0.001, 1 in 1000). Thus the lower the p value the less likely that a type 1 error has been made.

🔸As the sample size of a study increases, the P-value will decrease.

🔸The probability of not detecting a minimum clinically important difference if in truth there is a difference or of accepting the null hypothesis when it should have been rejected is denoted as β, or the probability of type II error. It is similar to the false negative result of a clinical test.

🔸The typical value of β is set at 0.2. The power of the study, its complement, is 1-β and is commonly reported as a percentage. Studies are often designed so that the chance of detecting a difference is 80% with a 20% (β = 0.2) chance of missing the Minimum Clinically Important Difference (MCID)

🔸This power value is arbitrary, and higher power is preferable to limit the chance of applying false negative (type II error) results.

🔸Type II errors are more likely to occur when sample sizes are too small, the true difference or effect is small and variability is large.

🔸The belief is that the consequences of a false positive (type I error) claim are more serious than those of a false negative (type II error) claim, so investigators make more stringent efforts to prevent this type of error

🔸At the stage of planning a research study, investigators calculate the minimum required sample size by fixing the chances of a type I or II error, strength of association and population variability. This is called “power analysis,” and the purpose is to establish what sample size is needed to assure a given level of power (minimum 80%) to detect a specified effect size.

🔸From this, one can see that for a study to have greater power (smaller β or fewer type II errors), a larger sample size is needed.

🔸Sample size, in turn, is dependent on the magnitude of effect, or effect size. If the effect size is small, larger numbers of participants are required for the differences to be detected.

🔸Determining the sample size, therefore, requires the MCID in effect size to be agreed upon by the investigators.

🔸It is important to remember that the point of powering a study is not to find a statistically significant difference between groups, but rather to find clinically important or relevant differences.

🔻N.B. The odds ratio is the ratio of the odds of the event happening in an exposed group versus a non-exposed group. The odds ratio is commonly used to report the strength of association between exposure and an event. The larger the odds ratio, the more likely the event is to be found with exposure. The smaller the odds ratio is than 1, the less likely the event is to be found with exposure.

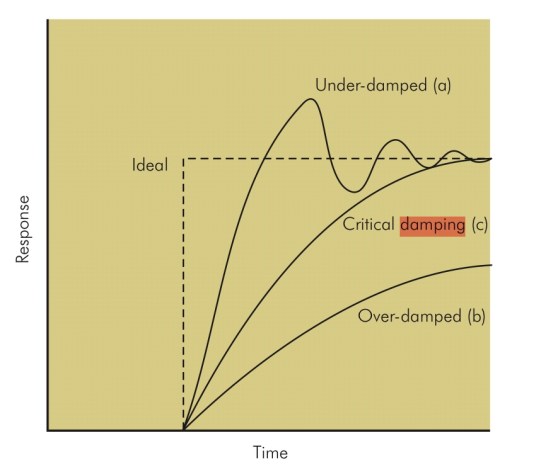

Damping

- Damping describes the resistance of a system to oscillation resulting from a change in the input. Damping is the result of frictional forces working in that system. So following a change in input there are several possible outcomes for the system:

- Perfect Response: any change in input would be instantly and accurately reflected in the output

- Under-damped – the output changes quickly in response to the step up in input, but it overshoots and then oscillates around the true value, before coming to rest at it. It will take some time before the true value is displayed and the peaks and troughs will over and underrepresent the true value. In a dynamic system, e.g. intra-arterial BP, the constantly changing input may result in wild fluctuations, rendering an under-damped system very inaccurate (although the MAP is still correct).

- Critically damped – the response and rise time of the system are longer than an under-damped response, but there is no significant overshoot and oscillations are minimal. ‘D’ is the damping factor and, by convention, in a critically damped system D = 1.

- Over-damped – defined as damping greater than critical. The output here could potentially change so slowly that it never reaches the true value. In a dynamic system, the response time may be too slow for the system to be useful.

- Optimally damped – in reality in clinical measurement systems, critical damping is not ideal and we are prepared to accept a few oscillations and some overshoot to achieve a faster response time. Hence, our systems are ‘optimally damped’ where 64% of the energy is removed from the system and D = 0.64. There is a 7% overshoot in this case.

- N.B: The ‘response time’ is the time taken for the output to reach 90% of its final reading. The ‘rise time’ is the time taken for the output to rise from 10 to 90% of its final reading.

- All instruments will possess damping that affects their dynamic response. This includes mechanical, hydraulic, pneumatic and electrical devices. In an electromechanical device such as a galvanometer there are mechanical moving parts such as the meter needle and bearings. Damping in these components arises from frictional effects on their movement. This may arise unintentionally or may be applied as part of the instrument design to control oscillation of the needle when it records a measurement. In a fluid (gas or liquid) operated device, damping occurs due to viscous forces that oppose the motion of the fluid. In an electrical system, damping is provided electronically by electrical resistance that opposes the passage of electrical currents.

- Damping is an important factor in the design of any system. In a measurement system it can lead to inaccuracy of the readings or display:

- Under-damping can result in oscillation and overestimation of the measurement.

- Over-damping can result in underestimation of the measurement.

- Critical damping is usually an optimum compromise resulting in the fastest steady-state reading for a particular system, with no overshoot or oscillation.

Drowning: Specific points

- Drowning is death while submerged in water, and near-drowning is suffocation while submerged with survival (at least temporary).

- If water does not enter the airway, asphyxia is the main complication.

- If the patient inhales water, marked intrapulmonary shunting & significant V/Q mismatching because of loss of pulmonary surfactant (wash-out) and reflex laryngobronchospasm are also mechanisms

- Significant volumes of hypotonic fresh water aspiration can lead to hyponatremia and hemodilution.

- Cold water drowning leads to loss of consciousness at a temperature below 32°C and ventricular fibrillation can occur at 28° to 30°C. Resuscitation efforts may be very prolonged after cold water aspiration

- Aspiration of gastric contents because of unconsciousness and lack of airway reflexes can further complicate lung injury and risk of death.

- All patients will have hypoxemia, hypercarbia and metabolic acidosis from lack of oxygen delivery and subsequent lactic acid production.

- Also Cerebral edema, ALI, and ARDS can complicate medical courses

- Treatment: restore spontaneous circulation and ventilation, focus on improving oxygen delivery further to decrease metabolic acidosis. Because of a significant risk of ALI and ARDS, airway management and lung protection ventilation strategies should be initiated as soon as possible. Cerebral protection maneuvers should also be followed and neurosurgical consultation obtained when appropriate. Electrolyte and temperature derangements should be treated. Patients’ clinical courses will be labile.

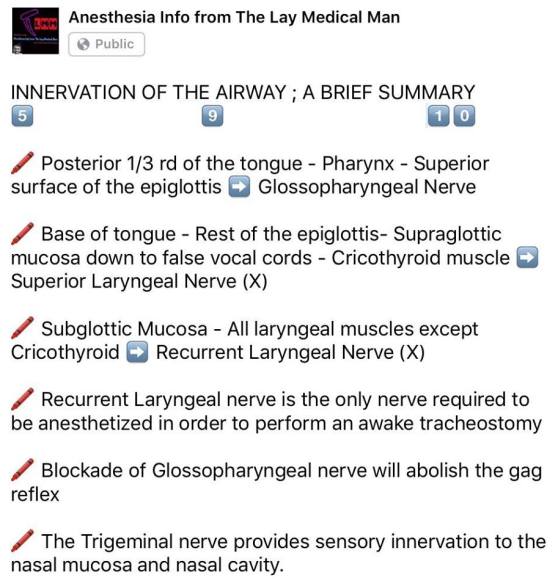

VIVA SCENE: NERVE SUPPLY OF AIRWAY / LARYNX

Morphine and Hydromorphone

- Morphine is metabolised via hepatic system and excreted by renal system

- It can get accumulated in hepatic/renal dysfunction and obesity

- Morphine has 2 metabolites:

- Morphine 6 glucoronide- Active metabolite: responsible for analgesia and sedation

- Morphine 3 glucoronide: Can cause seizures

- Morphine has histamine releasing property

- Hydromorphone is more potent than morphine

- Hydromorphone doesnt have active metabolites

- Hydromorphone lacks histamine release

CLOSING CAPACITY

FUNCTIONAL RESIDUAL CAPACITY [FRC]

The functional residual capacity of the infant’s lungs is only one half that of an adult in relation to body weight. This difference causes excessive cyclical increases and decreases in the newborn baby’s blood gas concentrations if the respiratory rate becomes slowed because it is the residual air in the lungs that smooths out the blood gas variations.

The functional residual capacity equals the expiratory reserve volume plus the residual volume. This is the amount of air that remains in the lungs at the end of normal expiration (about 2300 milliliters).