Atrial fibrillation(AF) is a supra-ventricular arrhythmia characterized by the complete absence of co-ordinated atrial contractions. There will not be any discernable p-waves.

The ventricular response rate depends on the conduction of the AV node.

WHAT IS THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN ATRIAL FIBRILLATION AND ATRIAL FLUTTER

Flutter is a more organised and regular form of atrial activity and classically with an atrial rate of 300 bpm. ‘Saw toothed’ flutter waves are present on the ECG. The ventricular response depends on conduction through the AV node. The classic ECG has 2:1 block, hence a ventricular rate of 150 bpm

CAUSES OF AF IN THE PERIOPERATIVE SETTING

Electrolyte abnormalities especially low potassium or magnesium

Withdrawal of beta blockers

Following cardiac surgery.

ASD or mitral valve disease

Ischaemic heart disease

Thyrotoxicosis

Excess caffeine or alcohol (acute or chronic)

Pulmonary embolism

Pneumonia

Pericarditis

In the context of major vascular surgery, systemic inflammation,hypovolemia and a heightened adrenergic state are likely to play a major role.

WHAT IS LONE AF?

‘Lone AF’ is AF in the absence of any demonstrable medical cause, but this is not usually diagnosed in the peri-operative period. So beta blockers will be efficacious in this setting.

WHAT ARE THE PROBLEMS AF CAN POSE?

Loss of the atrial ‘kick’ as it contracts and empties into the LV can reduce the CO by 10%–20% with a normal ventricle (reduced by 40%–50% in those with a ‘stiff’ ventricle as in

diastolic dysfunction, aortic stenosis etc). The disorganised contractions of the atria cause stasis of blood and the risk of thromboembolism. There is a 3%–7% annual risk of

thromboembolic CVA

AF- EVALUATION

*History *Assessment of volume status and electrolytes *ECG: This will also help to exclude acute ischaemia. *The pulse will be irregularly irregular. *No ‘a wave’ in the jugular venous pulsation as this is caused by sinus atrial contraction. *Chaotic atrial activity can be seen on echocardiography.

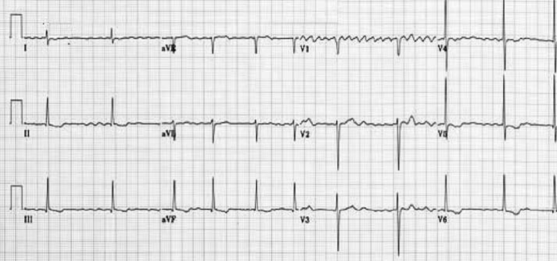

READ THIS ECG

MNEMONIC ‘RIAS QRST’ (Rate & Rhythm, Intervals, Axis, QRS & ST segment T wave)

The rate is 78 bpm; the rhythm is irregularly irregular. There are flutter waves seen in the V1 rhythm strip. The axis is normal (There is borderline LVH by voltage criteria). There are no Q waves and the QRS width is normal. There is evidence of infero-lateral ischaemia shown by the inverted and biphasic T waves in this territory (II, III, aVF and V3−V6).

MANAGEMENT OF AF

Assess for cardiovascular compromise and resuscitate simultaneously if needed. Oxygen should be administered, continuous ECG monitoring instituted and IV access secured.

If the patient is unstable, synchronised electrical cardioversion should be used to treat the arrhythmia.

In a stable patient, treatment options include: Rate control by drug therapy. Drugs used to control the heart rate include beta-blockers, digoxin, magnesium, the non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (verapamil or diltiazem) or a combination of these.

Rhythm control by amiodarone to encourage cardioversion: Amiodarone is given as a 300 mg IV bolus, followed by 900 mg IV over 24 hours.

Rhythm control by electrical cardioversion: This is more likely to restore sinus rhythm than chemical cardioversion.

Treatment to prevent complications. Patients who are in AF are at risk of atrial thrombus formation and should be anticoagulated

Patients who have pre excitation syndromes with an accessory conduction pathway between the atria and ventricles (such as in the Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome) should not be given AV node blocking drugs if they develop an SVT. This will promote the atrial impulses to travel directly to the ventricle at up to 300 bpm via the accessory pathway. The drugs of choice are amiodarone, flecainide or procainamide.

BEFORE PROCEEDING WITH DC CARDIOVERSION FOR AF, WHAT ALL THINGS SHOULD BE CONSIDERED?

- Cardioversion should only be attempted without anticoagulation if the duration of the AF is less than 48 hours. If the duration is unknown or longer than this, 3–4 weeks of anticoagulation (INR 2–3) is required to reduce the incidence of clot embolisation. If there is a contra-indication to anticoagulation, or if the cardioversion is deemed necessary more urgently, then an echocardiogram is needed to exclude thrombus in the atrium and atrial appendage

- When did the AF start (history of palpitations or recording on monitor): is it acute or chronic?

- What is the likelihood of an atrial thrombus which could be embolised by

cardioversion? - What is the ventricular rate now? – may need pacing after cardioversion if

the rate is below 60 bpm - Has there been an ischaemic episode?

ANESTHESIA FOR CARDIOVERSION

This should be done in a critical care or operating room area with the usual preparation, equipment and assistance needed for any routine anaesthetic. Someone independent should be present to perform the defibrillation, preferably with a hands-free device. Elective cardioversion has been done under conscious sedation without any adverse effects, but the usual technique is to use a sleep dose of propofol following pre oxygenation. One can use a facemask or maintain the airway with an LMA. If there is any serious doubt about cardiovascular performance or reserve, an arterial line should be given consideration, but this is a short procedure and the cardiac output should improve with the restoration of sinus rhythm. If the patient has a pacemaker in situ or an implantable cardiac defibrillator, we should place the paddles as far away as possible from the device and preferably in the anterior–posterior position.

IF THE PATIENT DOES NOT GET CARDIOVERTED, WHAT SHOULD YOU DO?

Try a period of 4–6 weeks of medical therapy and anticoagulation. If the patient is still in AF, then a further trial of DCC is reasonable. If a second DCC is unsuccessful, then rate control is the next step to improve symptoms and reduce ventricular failure.