Category Archives: Anesthesia

TIVA IN NEUROANAESTHESIA

SAFE & APPROPRIATE ADMINISTRATION OF TIVA

AEP Episode 1: SSI and prevention of infection in the ICU

Anaesthesia Exam Podcast: Crystalloids vs Colloids

Bridging Anticoagulation

Bridging anticoagulation consists of the substitution of a long-acting anticoagulant (usually with warfarin) for a shorter-acting anticoagulant (usually LMWH) to limit the time of subtherapeutic anticoagulation levels and minimize thromboembolic risk. Despite the growing evidence about the limited to nonexistent benefits of bridging therapy, it is still being used on a case-by-case basis. Clinical scenarios that may benefit from bridging therapy are those involving patients with high thromboembolic risk. In several guidelines, the following scenarios have been proposed:

- The patient with a mechanical heart valve: Mitral valve replacement, aortic valve replacement with additional risk factors (stroke, TIA, cardioembolic event, or intracardiac thrombus), more than 2 mechanical valves.

- Patients with stroke, episode of systemic emboli, or VTE during the last 3 months. Patients presenting with a thromboembolic event after interruption of chronic anticoagulation therapy or those presenting with VTE while on therapeutic anticoagulation.

- Patients with atrial fibrillation and CHA2DS2VASc score > 5 plus additional cardiovascular risk factors (rheumatic valve disease, stroke, or systemic embolism within the last 12 weeks). A CHA2DS2VASc score > 6 with or without additional risk factors.

- Patients with recent coronary stenting (within the previous 12 weeks)

How to bridge?

During the preoperative period:

- Discontinue warfarin five days before surgery.

- Three days before surgery, start subcutaneous LMWH or unfractionated heparin (UFH), depending on the renal function of the patient at therapeutic doses.

- Two days before surgery assess INR, if greater than 1.5 vitamin K can be administered at a dose of 1 to 2 mg.

- Discontinue LMWH 24 hours before surgery or 4 to 6 hours before surgery if UFH.

During the postoperative period:

- If the patient is tolerating oral intake, and there are no unexpected surgical issues that would increase bleeding risk, restart warfarin 12 to 24 hours after surgery.

- If the patient received preoperative bridging therapy (high thromboembolic risk) and underwent a minor surgical procedure, resume LMWH or UFH 24 hours after surgery. If the patient underwent a major surgical procedure, resume LMWH or UFH 48 to 72 hours after surgery.

- Always assess the bleeding risk and adequacy of homeostasis before the resumption of LMWH or UFH

N.B. : In 2019, a new strategy was published in the PAUSE study, a prospective clinical trial evaluating a standardized approach for perioperative management of DOACs. The interruption scheme used in this study was simple. For high bleeding risk procedures, rivaroxaban, apixaban, and dabigatran were suspended 48 hours before surgery in patients with CrCl>50 ml/min. If the renal function was compromised (CrCl< 50 ml/min), these drugs were interrupted for four days before surgery. For low bleeding risk procedures, rivaroxaban, apixaban, and dabigatran were interrupted 24 hours before surgery in patients with CrCl>50 ml/min. If the renal function was compromised (CrCl <50 ml/min), drugs were suspended two days before the procedure. Regardless of renal function, all drugs were reinitiated at 48 hours for high bleeding risk surgical procedures and 24 hours for low bleeding risk procedures. The 30-day postoperative rate of major bleeding was 1.35% (95% CI, 0%-2.00%) and rate of arterial thromboembolism of 0.16% (95% CI, 0%-0.48%). However, more studies are needed in patients with high surgical bleeding risk, before implementing this in regular clinical practice

Reference:

Perioperative Anticoagulation Management – StatPearls – NCBI by Polania Gutierrez JJ, Rocuts KR. · 2021

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557590/

Complications of Laparoscopy

- The commonest structure that can be injured by the laparoscope is the distended stomach. So pass a nasogastric tube and aspirate the stomach contents especially if the induction has involved prolonged bag and mask ventilation.

- Regurgitation of gastric contents can happen

- Pulmonary oedema from fluid infusions and the head-down position

- Insufflation is the most hazardous phase; A demonstrable gas embolism can occur in 1 out of 2000 patients; so watch for high insufflating pressures and low flow. Signs of gas embolism include arrhythmia, hypotension, cyanosis and cardiac arrest. The safest technique is to use CO2 for the pneumoperitoneum rather than N2O, because CO2 is more soluble and if an embolism occurs, it will resolve faster. Watch the indicators on the insufflating machine continuously during inflation. Pressure over 3 kPa or total volume insufflated exceeding 5 litres are hazardous. Caval compression and reduced venous return, with lowered cardiac output, may be a consequence of intra-abdominal pressure exceeding 4 kPa.

- The pressure effect of the insufflating gas will also splint the diaphragm and impede the mechanism of breathing.

- Avoid excessive head down tilt, and always be prepared for laparotomy.

- The end-tidal CO2 will rise during the course of a prolonged procedure and minute volume should be adjusted to compensate.

- Pneumothorax and surgical emphysema have been described, associated with prolonged surgery.

- Shoulder-tip pain, from diaphragmatic irritation, is a common postoperative problem.

DIFFERENCES BETWEEN THE TYPES OF HYPOXIA

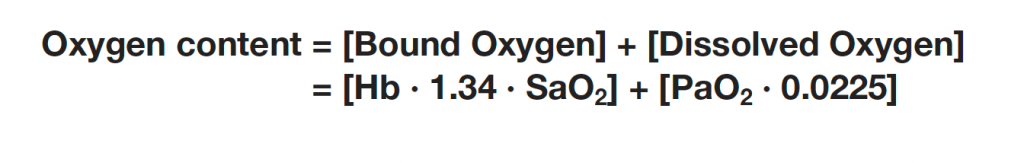

HYPOXIC HYPOXIA (e.g. High Altitude)

- PaO2 is reduced ( as FiO2 is low)

- So more extraction of O2: So PvO2 is reduced

- Based on the above formula, both arterial and venous oxygen content also will be reduced

ANAEMIC HYPOXIA (e.g. haemorhhage)

- PaO2 will be normal

- But arterial oxygen content will be reduced due to lower values of Hb, as per the above formula reducing the oxygen delivery to tissues and increasing the cardiac work

- So there will be more oxygen extraction leading to a low PvO2 and venous oxygen content.

STAGNANT HYPOXIA (e.g. Cardiogenic shock)

- PaO2 is normal

- PvO2 is also normal

- There is no reduction in the arterial and venous oxygen content too.

- However, circulatory dysfunction results in inadequate oxygen delivery to organs

HISTOTOXIC HYPOXIA (e.g. Cyanide poisoning)

- PaO2 is normal. Arterial oxygen content also will be normal.

- But cells are unable to utilise oxygen resulting in high venous saturations

Volume of Distribution

- Is the theoretical volume into which a drug must distributes to produce the measured plasma concentration

- Unit is mL

- It is measured as Vd= Dose / Co, where Co is the initial plasma concentration from a concentration-time graph

- Lipid solubility, plasma protein binding, tissue protein binding, regional blood flow etc determine the Vd

Acidic and Basic drugs

DO YOU KNOW❓

3 drugs with delayed recovery are weak bases: Diazepam, Midazolam & Etomidate (pKa ranging from 3-6)

5 drugs which are potent analgesics are strong bases: Morphine, Fentanyl, Ketamine, Bupivacaine, Lignocaine (7.5-8.5)

4 most commonly used drugs are weak acids: Paracetamol, Propofol, Atropine, Thiopentone (7.5-11)

LASI (lasix) and SALI (salicylic acid) are strong acids (3-4)

At pH < pKa, acidic drugs become less ionised:

HA ⇌ H+ + A–

At pH < pKa, basic drugs become more ionised as they accept protons:

B + H+ ⇌ BH+

Drugs cross membranes in the un-ionised state and so their pKa and the pH of the surrounding environment affect their rate of absorption. Hence, acidic drugs will be more readily absorbed in the highly acidic stomach, whereas basic drugs are better absorbed in the intestine where pH is higher.

Note: You can not find from pKa whether a drug is acidic or basic