The examination aims to assess a candidate’s knowledge of:

•The basic sciences

•Clinical anaesthesia (including obstetric anaesthesia & analgesia)

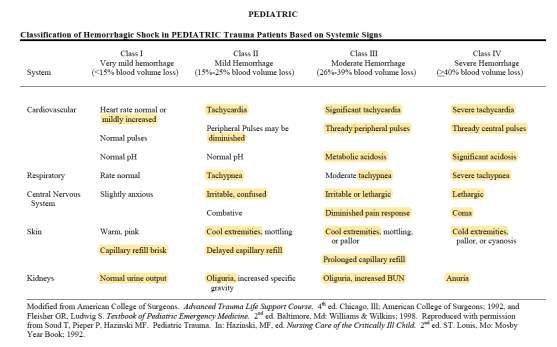

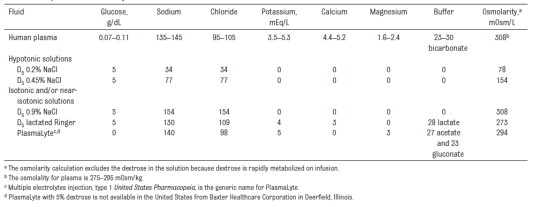

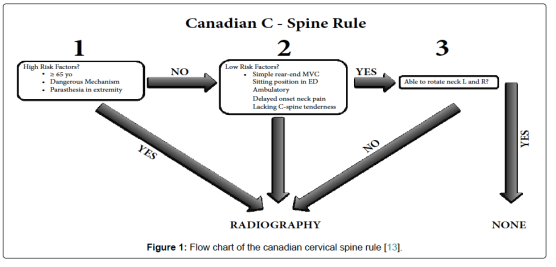

•Resuscitation and emergency medicine

•Specialist anaesthesia (e.g. neuro-, cardiac, thoracic, paediatric)

•Intensive care

•Management of chronic pain

•Current literature

BASIC SCIENCES

- anatomy, biochemistry, physiology, applied physiological measurement, pharmacology, physics and principles of measurement, STATISTICS

CLINICAL ANESTHESIOLOGY

- preop assessment, GA & RA , postop care NEONATAL RESUSCITATION RESUSCITATION & EMERGENCY MEDICINE

- Basic Life Support and Advanced Life Support. Pre-hospital care. Immediate care of patients with medical or surgical emergencies, including trauma

INTENSIVE CARE AS FOLLOWS:

- Both acute surgical and medical conditions.

- Use of assessment and prognostic scoring systems.

- Parenteral and enteral nutrition.

- Biochemical disturbances such as acid base imbalance, diabetic keto-acidosis, hyperosmolar syndrome and acute poisoning.

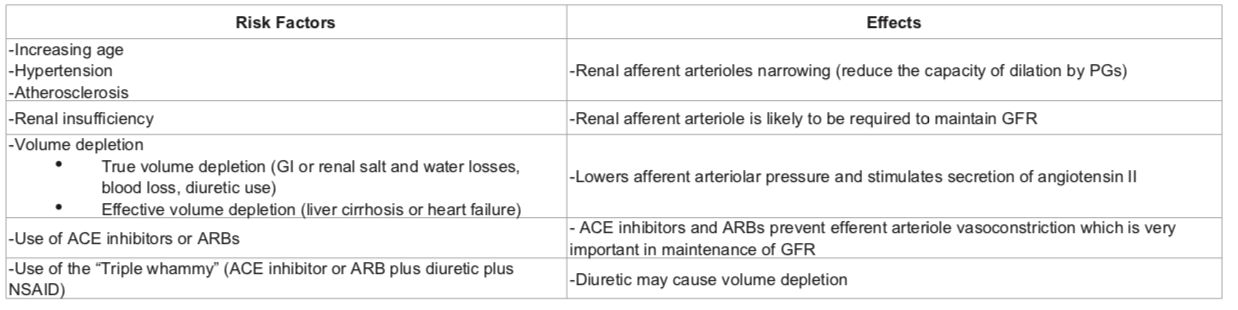

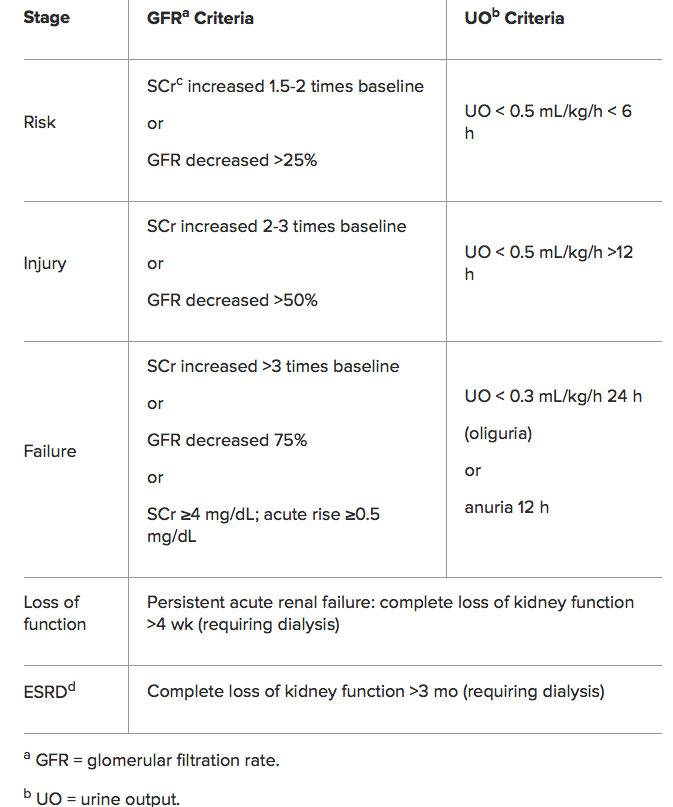

- Renal failure including dialysis.

- Acute neurosurgical/neurological conditions.

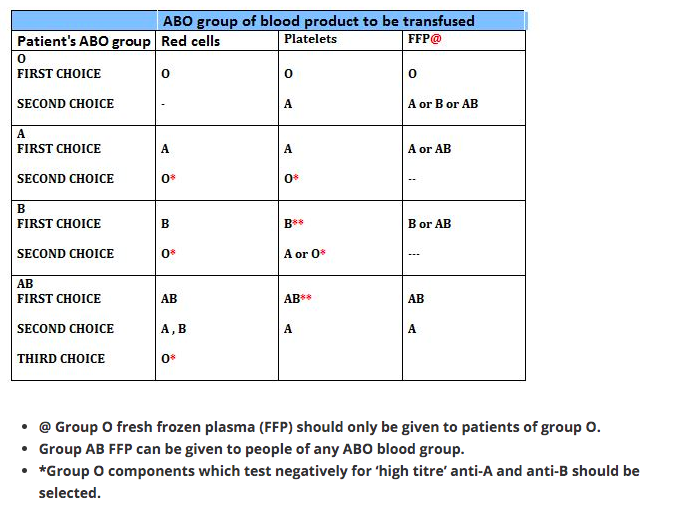

- Patients with multiple injury, burns and/or multi-organ failure.

- Principles of ethical decision-making.

MANAGEMENT OF CHRONIC PAIN AS FOLLOWS:

- The physiology of pain.

- management of pain.

- The concept of multidisciplinary care.

- Terminal care

- CURRENT LITERATURE

Candidates will be expected to be conversant with major topics appearing in current medical literature related to anaesthesia, pain relief and intensive care.

Whilst national and linguistic differences are recognised, some knowledge is expected on topics of international importance (e.g. new agents) even if they are not in current use in all countries.

It must he stressed that the foregoing is NOT intended either as an examination syllabus or as a comprehensive list of topics covered by the examination. It is however, a guide, which it is hoped will prove useful to candidates preparing for the diploma examination

GUIDANCE FOR CANDIDATES SITTING THE PART II EDAIC (2019)

The Part II EDAIC is an oral examination. Not all candidates are familiar with this type of examination and the following notes are intended to provide some guidance with regard both to preparation and to performance on the day.

The examination of each candidate is held in a single day during which there are four 25-minute oral examinations – (or vivas, as they are known) – two in the morning and two in the afternoon. In each of these, the candidate is examined by a pair of examiners, thereby meeting eight examiners in all. As far as possible, candidates are not examined by examiners from their own training hospital. The two morning vivas concentrate on applied basic sciences and the afternoon vivas relate to clinical topics.

Usually, but not invariably, each pair of examiners comprise one whose mother tongue is that of the language in which the candidate has chosen to be examined and the other who has a good working knowledge of the language. It is accepted that candidates may not be using their mother tongue and some allowance for linguistic difficulties is made.

In the vivas, the examiners use “Guided Questions” (GQ’s) which have been set in advance by the examination committee. Each GQ opens with a brief scenario. Ten minutes before the viva, the scenario is handed to the candidate. It is written in his/her chosen language. This gives the candidate time to collect his/her thoughts and prepare to answer questions on the topic presented. These opening questions are then followed by questions on the other topics listed in the examiner’s GQ. The first examiner asks questions for the first 12½ minutes after which a bell rings and the second examiner takes over.

Note that, whereas the Part I EDAIC basic science MCQ’s are designed to test factual recall of relevant basic science knowledge, the Part II basic science vivas are designed to test that the candidate understands the relevance of basic science knowledge applied to the practice of anaesthesia and critical care. Thus pharmacology, physiology, anatomy and relevant clinical measurement and instrumentation will always be tested. Similarly, the Part I EDAIC clinical MCQ papers are mainly concerned with testing the candidate’s factual clinical knowledge whereas the Part II clinical vivas are concerned with testing the understanding and application of that knowledge

CURRENT FORMAT OF THE EDAIC PART II EXAMINATION (2019)

The GQ’s with which the examiners are supplied list topics to be discussed with indications as to the detail required. The general format of the exam is as set out below.

MORNING

Viva 1 (Applied Basic Science)

This will start with the scenario the candidate was given 10 minutes before the start of the viva and will include applied cardiovascular and/or respiratory physiology. It will then move on to applied anatomy and physiology of other organs and systems.

Viva 2 (Applied Basic Science)

This will start with the scenario the candidate was given 10 minutes before the start of the viva and will include applied pharmacology. It will then move on to clinical measurement, applied pharmacology/physiology combined.

AFTERNOON

Viva 3 (Clinical – Critical care subject)

This will start with questions on the intensive care or emergency medicine scenario the candidate was given 10 minutes before the start of the viva. Questions on the scenario will be followed by topics such as clinical management, X-ray/CT/MRI/Ultrasound images interpretation, anaesthetic specialties and general questions.

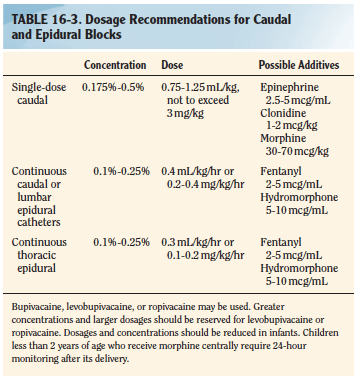

Viva 4 (Clinical – Management of an anaesthetic problem)

This will start with questions on the anaesthetic problem scenario the candidate was given 10 minutes before the start of the viva. Questions on the scenario will be followed by questions on an internal medicine topic – possibly related to the scenario. There will also be questions on local or regional anaesthesia and some general questions.

MARKING

For each of the 20 topics of the day, each examiner can award one of three marks, which indicate respectively:

Pass ‘2’. The candidate’s performance will be deemed: fluent, able to apply knowledge, confident on core topics, thorough and able to demonstrate appropriate depth, able to correct own errors,

Borderline ‘1’. The candidate’s performance will be deemed: showing factual knowledge only (book learning with no explanation, showing poor or incomplete understanding, superficial – particularly with core topics, erratic/unstructured/disorganized, illogical but with no dangerous clinical decisions.

Fail ‘0’. The candidate’s performance will be deemed: not answering question asked despite prompting or silence, showing evidence of severe lack of topic understanding, offering multiple answers for examiner to pick, having a dangerous clinical approach

All the marks of the eight examiners (two examiners for each four sessions) will be added up to make the final score of the candidate.

To be successful, the candidate needs to obtain:

1. a score of at least 25 out of 40 in the morning sessions (Viva 1 + Viva 2)

2. a score of at least 25 out of 40 in the afternoon sessions (Viva 3 + Viva 4)

3. an overall score of at least 60 out of 80

Thus, it can be seen that, at the meeting of examiners at the end of the day, in the majority of cases there need be no further discussion of individual candidates. However, if a candidate has obtained a final score of 59, the examiners concerned would be asked to justify the mark.

Some reasons for candidates failing include:

• Inability to apply knowledge and/or basic science to clinical situations

• Inability to organise and express thoughts clearly

• Unsound judgement in decision-making and problem-solving

• Lack of knowledge and/or factual recall

In essence the examiners ask themselves the following questions:

a) Does the candidate have a good foundation of knowledge? Can the candidate apply that knowledge and understand its relevance to the practice of anaesthesia and intensive care?

b) How does the candidate approach a problem? Is the approach logical and well thought out?

c) Have alternative options been explored and understood? Is the candidate dangerous?

The Part ll examination may only be taken after the candidate has completed his/her training for specialist accreditation in their respective country. A wide general knowledge in anaesthesia, intensive care and subjects allied to anaesthesia is therefore expected.

Background Reading

Which books shall I read? How much detail is required? These are common questions. There is no simple answer particularly since the EDAIC is an international exam, and the examiners and candidates come from different backgrounds. A basis for reading is the standard text book(s) of anaesthesia favoured in the candidate’s country. Familiarity with current topics from international and national journals is also be required. Access to journals may vary in different departments but the Internet now provides a wealth of new opportunities. In addition, a recommended reading is also at your disposal.

THE FOLLOWING ADDITIONAL POINTS MAY BE OF ASSISTANCE

Applied Basic Science Vivas

Physiology

It is obvious that the physiology of the cardiovascular and respiratory systems will be examined in some detail. A good knowledge of neuro, renal and hepatic physiology as applied to anaesthesia and intensive care will also be expected. Other areas relevant to anaesthesia will also be covered but great detail is not expected.

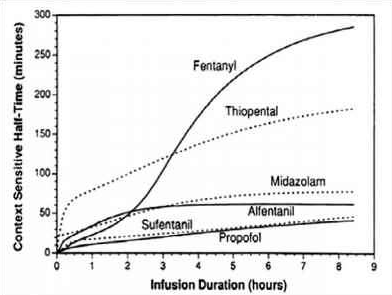

Pharmacology

The principles of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics will be examined in some detail. An intimate knowledge of the pharmacology and toxicology of drugs used in anaesthesia is expected as well as many of the drugs in common use in intensive care. An informed anaesthetist who reads journals must have some understanding of research protocols and the relevance of statistical methods employed, in order to judge the value of articles.

Applied Anatomy

It is expected that anaesthetists will know the essential anatomy of areas into which they may insert needles cannulae and endotracheal and endo-bronchial tubes. Applied anatomy of the heart and lung is also examined.

Physics and Clinical Measurement

Anaesthetists monitor and measure numerous clinical parameters and take action on the information displayed. It is expected therefore that they should understand the principle of action, limitations, accuracy, and sources of error in these monitors. Some of the basic physics of gases and vapours, and principles of electrical safety are essential knowledge for the informed anaesthetist. The principle of action and causes of failure in anaesthetic machines and ventilators is also essential knowledge.

Clinical Anaesthesia & Intensive Care Vivas

Clinical Anaesthesia

As candidates will have completed their training to the standard required for specialist registration they should have experience in all types of anaesthesia and intensive care. These vivas will include questions on both general, regional and special anaesthetic techniques as applied to neuro-, cardiac and paediatric surgery, obstetric anaesthesia and the management of acute and chronic pain.

The examiners do not have direct experience of how the candidate would deal with an anaesthetic problem. They therefore have to make a judgement based upon the candidate’s performance in the oral exam. The examiner cannot assume the candidate would have carried out a procedure or checked a clinical or electronic monitor. The candidate must mention it.

Clinical scenario

An example of the clinical scenario given in advance to a candidate would be as follows: A 67-year-old man weighing 100kg, 1.67m in height is scheduled for an elective repair of a 10cm abdominal aortic aneurysm. He had myocardial infarction 6 months previously and has been a non-insulin dependent diabetic for over 10 years. Discuss your anaesthetic management of this case.

The initial discussion on this sort of opening scenario will reveal much about the candidate’s approach to the problem and an awareness of the potential dangers. Remember that the anaesthetic management starts in the ward!

Definition of problems: Clearly, the primary problem is the presenting aneurysm and its repair. What will it involve?

Secondly the patient is obese and has, as yet unquantified, cardiovascular problems and diabetes.

This would lead to a full medical history with emphasis on the above with appropriate examination and investigation of potential complications. The anaesthetic management would involve choice of technique, appropriate monitoring, management of complications and post-operative pain relief.

A candidate who presents a logical well structured answer, explaining the reasons behind the proposed course of action, is more likely to find that the examiner says very little and does not have to interject continually. It cannot be emphasised enough that practice in presentation is essential and candidates should practice this skill with their trainers or fellow trainees. This is even more important for candidates not using their mother tongue

This topic alone, could take up more than the allotted time and so examiners may suddenly curtail discussion on a given subject and move on to something else. This is a necessary part of the examination process and does not indicate displeasure with the answers given.

Candidates should appreciate that the intention of the examiners is to enter into a dialogue with them regarding whatever topic is under discussion. The intention is not simply to find the candidate’s areas of ignorance although, inevitably, these may become apparent – if they exist. Bearing this in mind, the candidate should try to discuss the topic knowledgeably and should not be afraid to say when the topic is completely outside his/her experience. The EDAIC being an international exam and not a collection of national exams, means inevitably, that a wide range of views will be held both by the candidates and examiners.

It is assumed that candidates have been trained in standard mainstream anaesthetic techniques. They would be wise therefore to base their answers on methods with which they are familiar and would be normal in their institution, rather than straying into unfamiliar territory in the mistaken belief that this might be the answer the examiners require. Examiners will sometimes query an answer to see whether the candidate is confident in their answer or can be swayed from their course of action. There will often be no right or wrong answer to a question and examiners will accept an answer or opinion that is based on sound evidence and justifies the proposed course of action

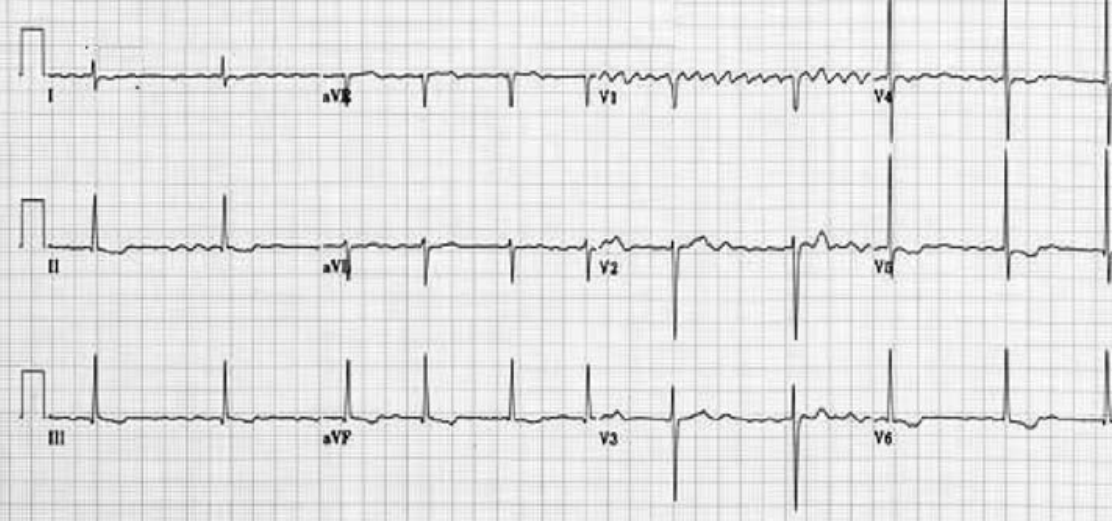

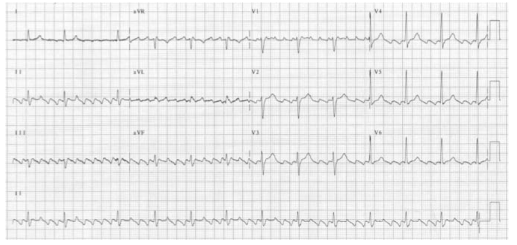

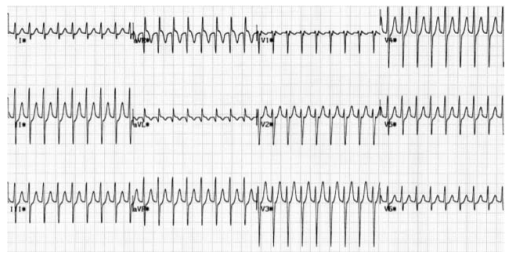

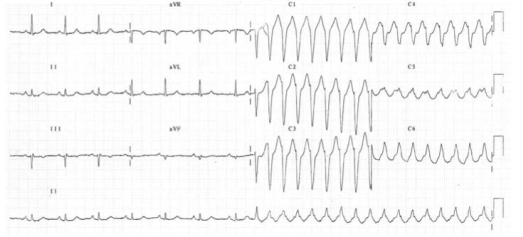

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW OF

Images

Candidates are expected to have a systematic and logical approach to reading Images and should be able to describe their system to the examiner. A typical system would be:

For example, for X-rays:

Markings: Look at writing on the film: name/age of the patient and projection of the radiograph.

Film Quality: Penetration, rotation & inspiration (on a chest film).

Review Areas: Lungs, diaphragm, pleura, upper abdomen, heart & mediastinum, bones of thoracic cage & soft tissues.

Artifacts: Note the presence of any equipment placed in the chest by anaesthetists or surgeons!

Recognition of Critical Incidents and taking prompt and appropriate action

One common cause for failure in the exam is a haphazard approach to dealing with critical situations that are posed and not following Advanced Life Support protocols. Airway, Breathing and Circulation should be the foundation of all resuscitation.

Diagrams & Graphs

Use of diagrams, graphs and other material to present answers. Pencils and paper are provided at all times during the Part II vivas. Candidates can use them to advantage in making presentations and explaining points. A typical scenario given in advance in the applied basic science exam might be: Discuss the factors that influence carriage of oxygen in the blood. A diagram of the various oxy-haemoglobin dissociation curves with some relevant values would create a good impression at the commencement of the exam and help the candidate settle into a structured answer. In pharmacology, the value of diagrams and graphs in explaining the principles of pharmacodynamics or pharmacokinetics is obvious .

N.B. For EDAIC 1

1-2 Questions from statistics will come in Part 1 Paper A

Statistics: Basic principles of data handling, probability theory, population distribution and the application of both parametric and non-parametric tests of significance.

GENERAL ADVICE ON PRACTISING FOR VIVAS (Basically for FRCA; but may be useful for EDAIC too)

We found the following techniques extremely valuable in the run-up to the vivas:

1.Group revision

2.Frequent practice

3.Practise categorising

4.Card system

- Group revision: It is extremely useful to team up with some friends or colleagues regularly in the weeks before the viva and practise talking about anaesthetic topics. Practising with friends has several advantages: Seeing your friends on a regular basis will help keep you sane. This is better than locking yourself in a small room with a pile of books and trying to learn the coagulation cascade for the fifth time since qualification! Your morale will remain in better shape than if you were revising on your own because you will be able to encourage each other. You will also be more aware of the progress you are making. As a group, you can pool your resources in terms of reference books and previous questions. During the working day, one of you may have had a practice viva with a consultant who asked an awkward question or a common question asked in a different way. You can then discuss with your friends how they would have answered it. Different people revise in different ways and, consequently, will have their own way of talking about a subject. This means that others in the group will benefit from listening to the practice viva. They may have a particular piece of knowledge that really helps an answer gel together or they may use a particular turn-of-phrase that succinctly deals with a potential minefield. You can practise phrasing your answers in a particular way in the knowledge that, if it all falls apart halfway through, it won’t matter and you can have another go. This is less easy to do in front of consultants who might write your reference! By being ‘the examiner’, you will gain insight into the pitfalls of the viva process. You can usually see someone digging a hole for themselves a mile off!

- Frequent practice: Repetition of clinical scenarios. During your revision, you will find the same clinical situations coming up time and time again (as in the exam). Over the years, anaesthetic techniques may change but new techniques are all aimed at trying to solve particular clinical problems, for example, the fibre-optic scope to help with the difficult airway or new drugs that provide more cardiovascular stability. However, the problems remain the same! Patients will still present with difficult airways, ischaemic heart disease, COAD, obesity, hypertension, etc. The more you practise, the more often you will find yourself repeating the problems each of these scenarios presents and thus the more confident and slick you will become at delivering the salient points. There are obviously a few exceptions, e.g. MRI scanners and laser surgery, where the advancement of technology has presented new challenges to the anaesthetist. These situations are in the minority and as long as you are aware of them and the associated anaesthetic problems, you should be well-equipped to deal with questions on them in the exam.

- The clinical scenarios break down into a few categories:

- Medical conditions that have anaesthetic implications, e.g. Aortic stenosis, Diabetes, Hyperthyroidism.

- Surgical procedures that have anaesthetic implications, e.g. Oesophagectomy, CABG, Pneumonectomy.

- Anaesthetic emergencies/difficult situations, e.g. Anaphylaxis, Malignant hyperthermia, Failed intubation. Paediatric cases. These represent a limited range of cases the examiners are likely to ask you about, e.g. Upper airway obstruction, Pyloric stenosis, Bleeding tonsil.

- Having repeatedly practised these clinical scenarios, you will soon realise that the problems of anaesthetising an obese patient with diabetes, ischaemic heart disease, porphyria and myasthenia for an abdominal aortic aneurysm repair (!) can be broken down into the problems that the respective conditions present to the anaesthetist, plus the problems of the specific operation. You may then approach what seems to be a nightmare question with a degree of confidence and structure.

- Phrasing: It cannot be over-emphasized that frequent practice will improve your viva technique. As already mentioned, some topics crop up again and again in different situations, such as part of a long case or even a complete short case (e.g. obesity, anaesthesia for the elderly or the difficult airway). With regular practice, you will soon develop your own ‘patter’ to help you deal with these common clinical scenarios. These can then be adopted at opportune moments to buy yourself easy marks whilst actually giving you time to gather your thoughts

- Practise categorising: Putting order to your answers demonstrates to the examiners that you conduct your clinical practice in a systematic and safe way. If you do not mention the most important points first (e.g. airway problems in a patient presenting with a goitre), then this may suggest to the examiners that you are disorganized. An ‘ABC’ (order of priority) approach to many of the questions may be helpful. For example, in obese patients, managing the airway has a higher priority than difficulty with cannulation. It is often a good idea to use your opening sentence to tell the examiners how you are going to categorize your answer.

Example 1:

‘Tell me about the anaesthetic implications of rheumatoid arthritis’.

‘Patients with rheumatoid arthritis may have a difficult airway and secondary respiratory and cardiovascular pathology. They are frequently anaemic, taking immunosuppressant drugs and the severe joint pathology leads to problems with positioning’.

Example 2:

‘What are the important considerations when anaesthetising a patient for a

pneumonectomy’?

‘These may be divided into three broad areas: the pre-operative assessment of fitness for pneumonectomy and optimisation, the conduct of anaesthesia with particular reference to one-lung anaesthesia, positioning, intra-operative monitoring and fluid balance and finally post operative care’.

- Card system: We formatted postcards to summarise the main problems associated with different anaesthetic situations. These proved to be a good starting point for viva practice and a quick source of reference. They also encouraged us to deliver the first few points in a punchy manner.

For example:

‘What problems do you anticipate with anaesthetising a patient with Down’s syndrome’?

‘These patients present the following problems for the anaesthetist. They may have a difficult airway, an unstable neck, cardiac abnormalities, mental retardation, epilepsy and a high incidence of hepatitis B infection’.

VIVA TECHNIQUE

- 1.Think first: Don’t panic. If you are unlucky enough to be asked a question about an obscure subject such as lithium therapy (as two of us were in our science viva), remember the examiners have only just seen the questions as well. It may also be of some comfort to know that there will be at least ten other candidates being asked the same question at the same time. Keep things simple at first and think about how you are going to structure your answer. Categorising your answer may allow you to deliver more information about the topic than you thought you knew. Conversely, do not dwell on what you do not know, e.g. the pH and dose!

Example: ‘Tell me about lithium’

Think . . . ‘What is it used for’?

Say . . . ‘Lithium is a drug used in the treatment of mania and the prophylaxis of manic depression’.

Think . . . ‘What is the presentation and dose? . . . I don’t know the dose’.

Say . . . ‘It is presented in tablet form’.

Think . . . ‘What is its mode of action? . . . I have no idea but I know it is an antipsychotic’!

Say . . . ‘Its main action is as an antipsychotic’.

Think . . . ‘Why are they asking me this question? What is the relevance to anaesthetic practice’?

Say . . . ‘It has a narrow therapeutic range and therefore toxicity must be looked for. Side effects may include nausea, vomiting, convulsions, arrhythmias and diabetes insipidus with hypernatraemia’.

A similar approach can be used for the clinical viva.

- The opening sentence : This will set the tone of the viva. If the first words to come from your mouth are poorly structured, ill thought-out or just plain rubbish, then you are likely to annoy the examiners and will face an uphill struggle. If, on the other hand, your first sentence is coherent, succinct and structured, then you will be half-way there. With a bit of luck, the examiners will sit back, breathe a sigh of relief (because it has been a very long day for them) and allow you to demonstrate your obvious knowledge of the subject in hand!

For example:

‘What are the problems associated with anaesthesia for thyroid disease’?

‘Anaesthesia for patients with thyroid disease has implications in the pre-, intra- and post-operative periods’.

You are then able to expand in a logical way from here.

‘Pre-operatively, assessment of the airway and control of the functional activity of the gland is essential . . . ’

Remember this lends structure to your answer and gives the examiners the impression you are about to talk about the subject with authority. If you categorise your answer well enough, they may actually stop you and move onto something else.

You will be asked to summarise the case so prepare your opening sentence

beforehand.

For example:

You may be asked to summarise the scenario of a 75-year-old man with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who is scheduled to undergo an elective cardio-oesophagectomy the following day.

‘Would you like to summarise the case’?

One possible answer may begin:

‘This is an elderly gentleman with complex medical problems who is scheduled for a cardio oesophagectomy. He has evidence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ischaemic heart disease and diabetes. There will be substantial strain on his cardio-respiratory system. This operation is a major procedure that involves considerable fluid shifts, a potential for large blood loss and requires careful attention to analgesia. These are the main issues that I would concentrate on in my pre-operative assessment’.

Even though a cardio-oesophagectomy involves other considerations (e.g. double-lumen tube / one-lung ventilation) it can be seen that this opening sentence could be adapted to suit other clinical scenarios such as:

Pneumonectomy

Laparotomy

CABG / valve replacement

Cystectomy

Open prostatectomy

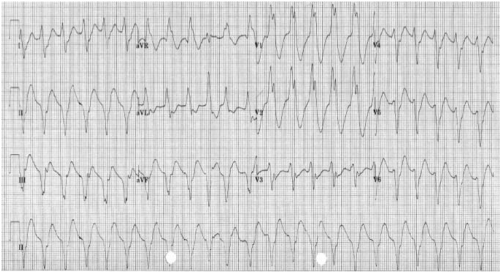

- Analyse all the investigations

You will be asked for your opinion on the ECG, chest X-ray, blood results, etc., so make sure you have decided on the abnormalities and the most likely causes for them in the 10 minutes you have to view the data. Try to make your answers punchy and authoritative.

For example, ‘The ECG shows sinus rhythm with a rate of 80 and an old inferior infarct’ is better than going through the ECG in a painstaking ‘The rate is . . . the rhythm is . . . the axis is . . . ’

Don’t waste valuable time waffling on about the normal-looking bones on a chest X-ray if there is a barn-door left lower lobe collapse. This does not necessarily imply you are not thorough, providing you demonstrate that you have looked for and excluded other abnormalities.

You will usually be asked how you would anaesthetise the patient in the long case. There will often not be a right or wrong answer, but you should try to decide on your technique and be able to justify it. The examiners may only be looking for the principles of anaesthesia for a particular condition such as aortic stenosis, although this is probably more likely in the short cases.

For example:

‘You are asked to provide an anaesthetic for a 77-year-old lady who needs a hemi-arthroplasty for a fractured neck of femur. She had a myocardial infarction 3 months ago and has evidence of heart failure’.

You should be able to summarise the principles involved and choose an anaesthetic technique appropriate to the problems presented. You could, for example, give this patient a general anaesthetic with invasive monitoring , you could use TIVA with remifentanil or a neuroaxial block.

All of these techniques could be justified, but to simply say that you would use propofol, fentanyl and a laryngeal mask without saying why, may be asking for trouble!

In some circumstances it may be the options for management rather than a specific technique that is required. You may find it appropriate to list the options for analgesia in a patient having a pneumonectomy, for example, and then say why you would use one technique over the others.

You should try to address the anaesthetic technique for the long case BEFORE you face the examiners. You will not look very credible if you have had 10 minutes to decide on this and have not reached some kind of conclusion. Overall, most candidates felt that the examiners were pleasant and generally helpful. If you are getting sidetracked they will probably give you a hint so you do not waste time talking about something for which there are no allocated marks. If they do give you a hint, take it!

Good luck.