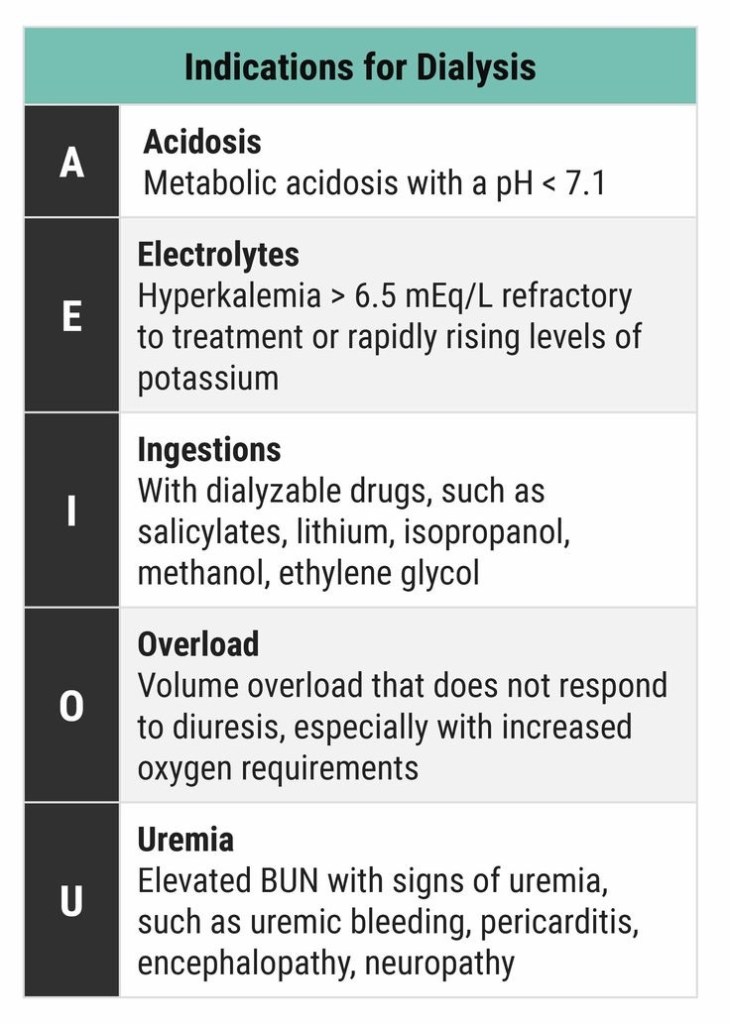

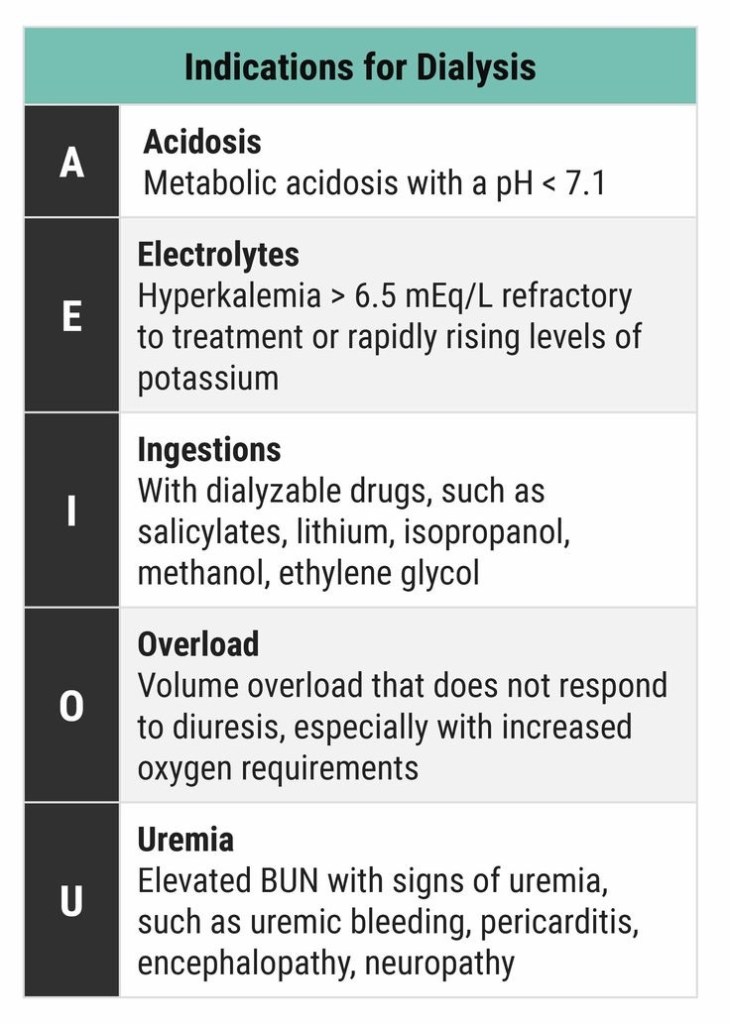

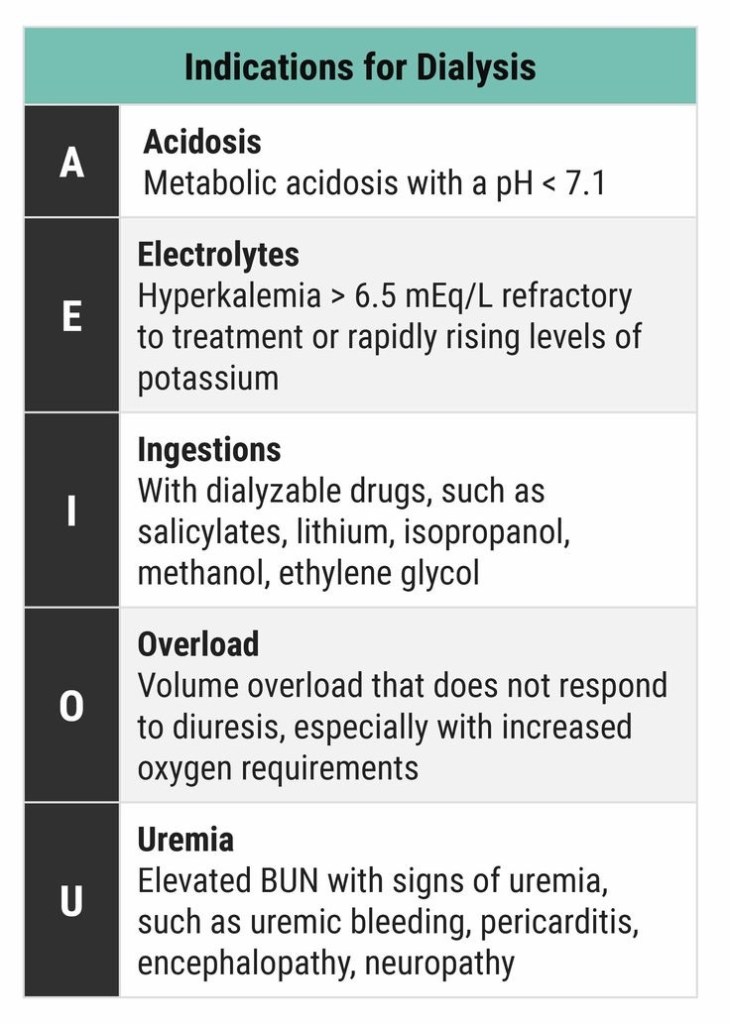

DIALYSIS INDICATIONS

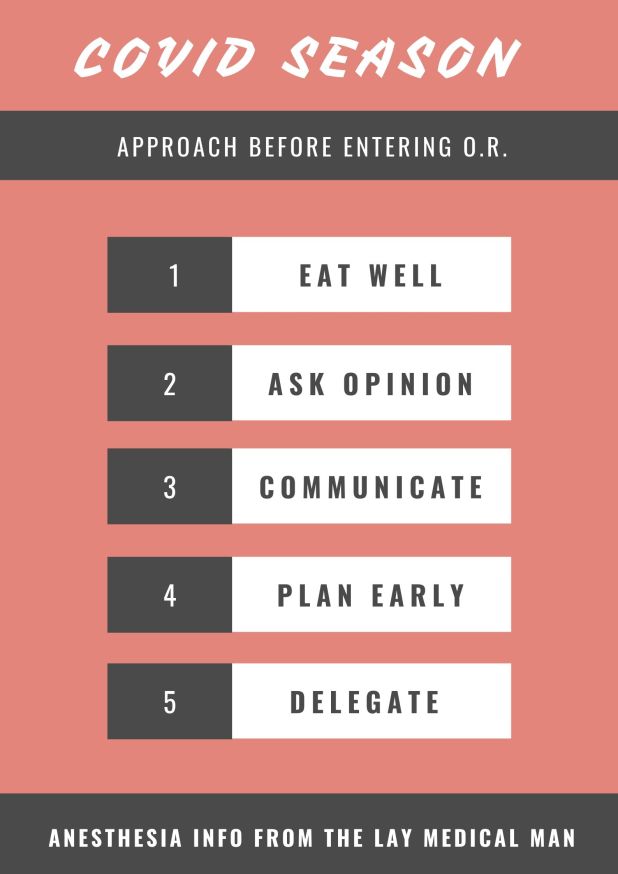

1.TAKE CARE OF YOURSELF

2.ASK OPINION TO SOMEONE WHO ALREADY HAD AN EXPERIENCE

3.GOOD COMMUNICATION BETWEEN ANESTHESIA & SURGERY TEAMS

4.PLAN SUFFICIENTLY EARLY AND DISCUSS INSIDE THE TEAM

5.ASSIGN DUTIES CLEARLY TO EACH MEMBER

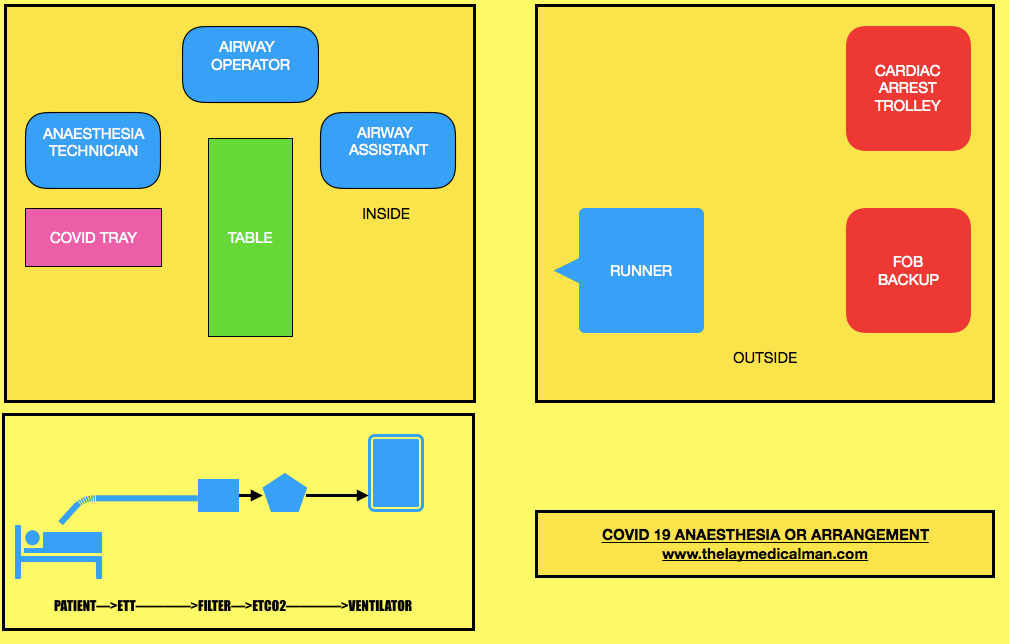

GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS FOR PERIOPERATIVE SCENARIO (Source: 1 Consensus guidelines for managing the airway in patients with COVID-19 Guidelines from the Difficult Airway Society, the Association of Anaesthetists the Intensive Care Society, the Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine and the Royal College of Anaesthetists, Source: 2 Editorial, anesthesia-analgesia, May 2020, Source: 3 Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation and World Federation of Societies of Anesthesiologists, accessed 3/13/2020, Source: 4 Interim guidance for health care providers during covid-19 outbreak from AHA and 5 CDC guidelines)

PREPARATION OF DRUG/ EQUIPMENT

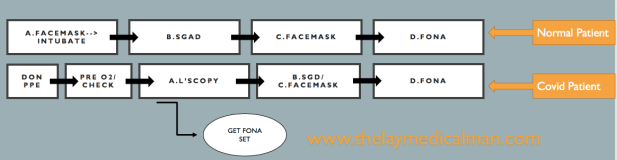

PROCEDURE:

EMERGENCY INTUBATION IN THE CRITICAL CARE UNIT (Source: 6 Wax, R.S., Christian, M.D. Practical recommendations for critical care and anesthesiology teams caring for novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) patients. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth(2020))

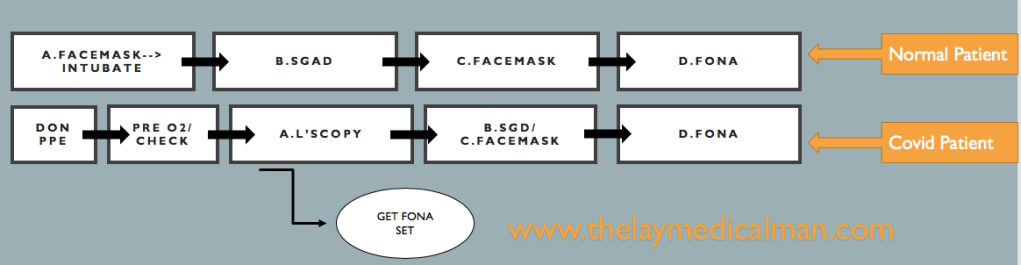

DIFFICULT AIRWAY

Compared to the normal patient, after the first failure of intubation itself, we should order for Front Of Neck Access (FONA) set. And in the next step, we can either do step B (SGD) or step C ( Facemask). Because of this, we will move fast towards the final step of FONA in the Covid difficult airway algorithm.

Prevention and management of respiratory or cardiac arrest: Protected Code Blue (PCB) (Source: 7 Resuscitation Council. Resuscitation Council UK Statement on COVID-19 in relation to CPR and resuscitation in healthcare settings. 2020. Source: 8 Wax, R.S., Christian, M.D. Practical recommendations for critical care and anesthesiology teams caring for novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) patients. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth(2020))

Lower risk resuscitation interventions:

| Placement of an oral airway |

| Placement of an oxygen mask with exhalation filter on patient (if available) |

| Chest compressions |

| Defibrillation, cardioversion, transcutaneous pacing |

| Obtaining intravenous or intraosseous access |

| Administration of intravenous resuscitation drugs |

Higher risk resuscitation interventions more likely to generate aerosol and/or increase risk of viral transmission to staff

| Bag-mask ventilation |

| CPAP/BiPAP |

| Endotracheal intubation/surgical airway |

| Bronchoscopy |

| Gastrointestinal endoscopy |

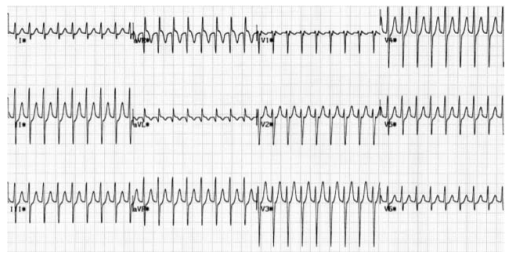

A broad complex tachycardia has a QRS complex greater than 0.12 seconds. They are usually ventricular in origin, but can also be supraventricular with aberrant conduction. Other possible causes for broad complex tachycardias include atrial fibrillation with ventricular pre-excitation, i.e. patients with Wolff–Parkinson–White (WPW) syndrome, or torsades de pointes (polymorphic VT).

Broad complex tachycardia is therefore due to SVT with aberrancy or Ventricular Tachycardia (VT), and differentiating between the two can be challenging. However, there are a few pathognomonic ECG features that diagnose VT

1.Atrio-ventricular (AV) dissociation. There is a higher ventricular rate than atrial rate (more QRS complexes than P-waves). This can only occur if the ventricular rate is autonomous and no longer under control of the SA node.

2.Capture beats: There is an isolated narrow complex amongst a train of broad complexes. This represents a normally conducted P-wave via the AV node and an intact His-Purkinje system indicating there is no underlying bundle branch block. Therefore, the train of broad complexes are ventricular in origin (i.e. VT).

3.Fusion beats: A normally conducted P-wave may fuse with a simultaneous ventricular beat causing a complex halfway between the appearance of a normal QRS and a broad complex.

4.VT is more likely in patients with a prior history of MI.

5.VT complexes are usually very broad (> 160 ms) due to a very abnormal path taken by the depolarisation wave from the VT focus.

6.The time from R-wave onset to the nadir of the S-wave is prolonged (> 100 ms) in VT, again representing an abnormal activation path through the ventricle.

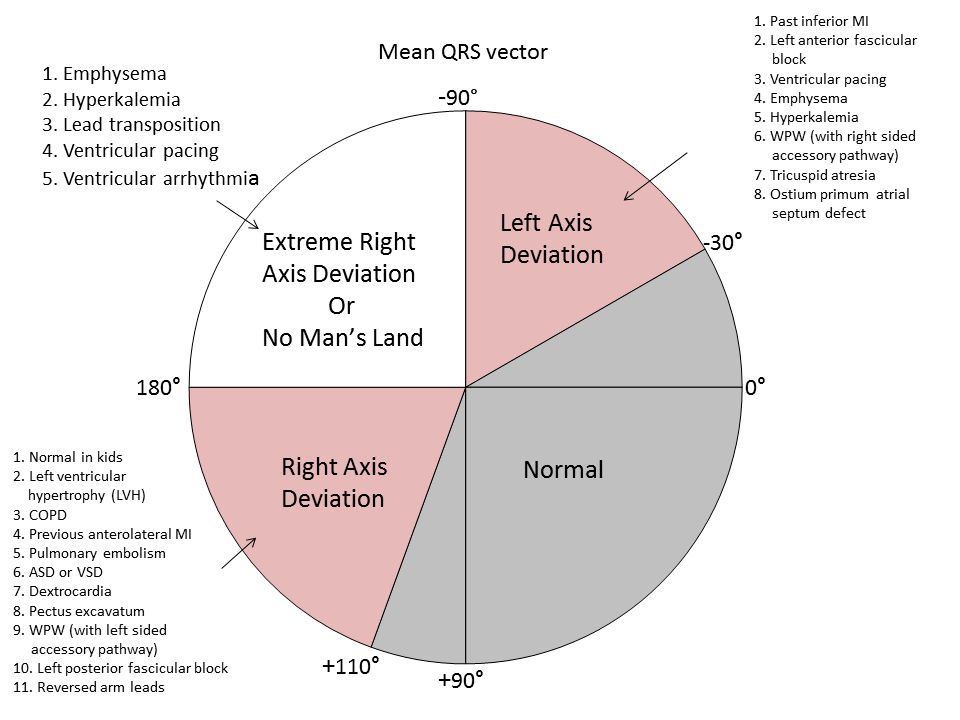

7.Extreme left axis deviation and positive aVR are more common in VT, as the ventricles are depolarised in the opposite direction to normal conduction.

8.Failure to respond to iv adenosine

9.The absence of typical RBBB or LBBB patterns suggests VT. For example, an RSR pattern in V1 with a taller first R-wave suggests VT (in RBBB the first R-wave is caused by septal depolarisation and is therefore smaller than the second R-wave, which is caused by depolarisation of the RV).

SVT with aberrancy is more likely if previous ECGs demonstrate an accessory pathway or a bundle branch block with identical morphology to the broad complex tachycardia. When in doubt, treat as VT

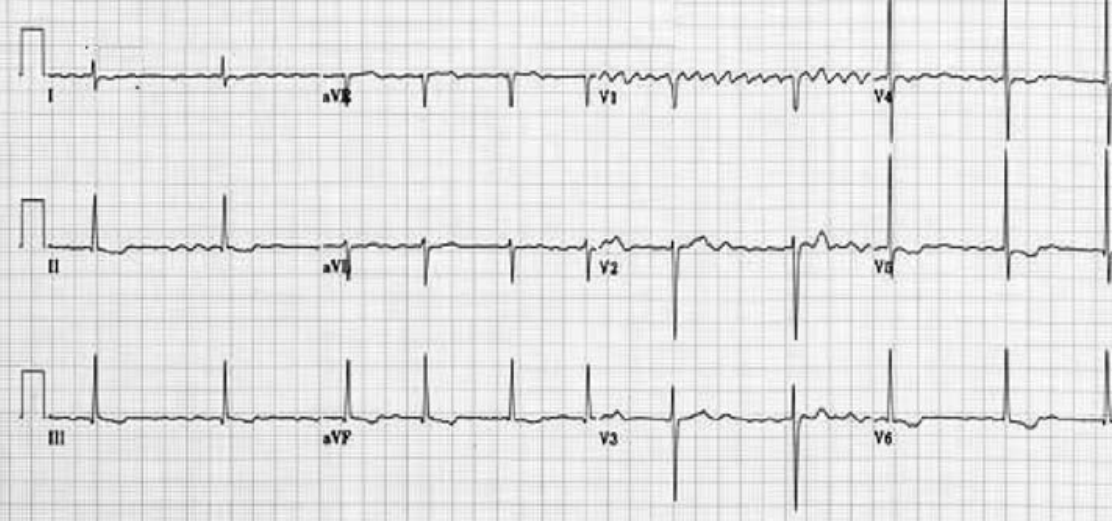

TORSADES DE POINTES

Is a specific variant of ventricular tachycardia (VT). It has a classic undulating pattern with variation in the size of QRS complex. It is caused by a prolonged QT interval and can precipitate VF and sudden death

QT PROLONGATION: CAUSES

Tricyclic antidepressants, flecainide and quinidine; Hypocalcemia; Acute myocarditis

VENTRICULAR TACHYCARDIA(VT) AND VENTRICULAR FIBRILLATION (VF)

VT is a broad complex tachycardia, defined as a run of at least three consecutive ventricular ectopic beats, at a rate of >120 bpm. Can arise from a single or multiple foci or from a reentry circuit. There may be capture or fusion beats, where a normally conducted beat will join an ectopic beat travelling in the opposite direction

CAUSES: Acute MI, degeneration of other arrhythmias, electrolyte abnormalities etc

VF describes an ECG which is random and chaotic with no identifiable QRS complexes that is incompatible with life and need immediate provision of ACLS with prompt delivery of DC shock. Others: Amiodarone, Lidocaine, beta blockers, Implantable cardioverter defibrillators

MANAGEMENT

For VT treat with amiodarone 300 mg IV followed by 900 mg over 24 hours. If the arrhythmia is known to be supraventricular, treat as a narrow complex tachycardia.

An irregular broad complex tachycardia is most likely to be atrial fibrillation with bundle branch block, and should be treated as narrow complex atrial fibrillation

In a stable patient who is known to have WPW, the use of amiodarone is probably safe. Adenosine, digoxin, verapamil and diltiazem must be avoided, as these drugs block the AV node and will cause a relative increase in pre-excitation

Torsades de pointes is treated by stopping all drugs known to prolong the QT interval and correcting electrolyte abnormalities. Magnesium sulphate (2 g IV over 10 minutes) should also be given. Such patients may require ventricular pacing. If the patient’s condition deteriorates proceed to synchronised electrical cardioversion or, if the patient is pulseless, commence the ALS algorithm

Ventricular bigeminy

Ventricular bigeminy is associated with endotracheal intubation (a sympathoadrenal response). Given time the bigeminy will disappear, but if it does not intravenous

lidocaine (50–100 mg) may be helpful

Narrow complex tachyarrhythmias have a QRS duration <0.12 seconds. They arise above the bundle of His.

NARROW COMPLEX TACHYCARDIA

As narrow complex tachycardias involve ventricular activation through the normal His-Purkinje system, they must originate within the atria and are therefore often referred to as supraventricular tachycardia (SVT). There are five common types of SVT. They are: Atrial tachycardia, Atrial fibrillation, Atrial flutter, Atrioventricular nodal

re-entry tachycardia, Atrioventricular re-entry tachycardia. When faced with an ECG of narrow complex tachycardia, (i) we should examine the P-wave and (ii) check the QRS regularity

SINUS ARRHYTHMIA/TACHYCARDIA/BRADYCARDIA (from SA Node)

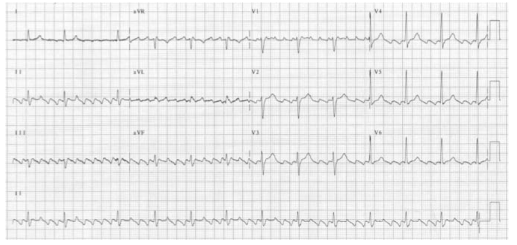

ATRIAL FIBRILLATION

There is completely disorganised atrial activity, with P-waves replaced by an irregular baseline due to fibrillation waves, and QRS complexes occur in an irregularly irregular fashion (Please the post on AF)

ATRIAL FLUTTER

There is a self-perpetuating wave of atrial depolarisation usually circulating within the right atrium, causing regular, saw-toothed flutter waves at 300 bpm and QRS complexes every second, third, or fourth flutter wave. We can see classical sawtooth flutter waves.Drug control of the ventricular rate is not often successful.

ATRIAL TACHYCARDIA

There is an abnormal atrial focus driving the ventricular rate. This rhythm can be difficult to distinguish from sinus tachycardia, but P-wave morphology and axis is usually abnormal. If the atrial focus is close to the AV node, a junctional tachycardia may occur and P-waves may be absent.

In case of Atrial tachycardia with AV block after halting glycoside therapy (and ensuring normokalaemia), lidocaine 1 mg kg−1 IV is the drug

of choice. Alternatively DC cardioversion or atrial

pacing may be effective.

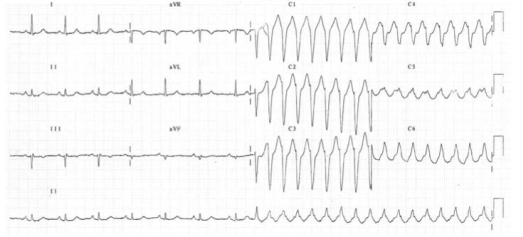

ATRIO VENTRICULAR NODAL REENTRY TACHYCARDIA (AVNRT)

This is the commonest type of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (PSVT). It is often seen in people without any heart disease, and is usually benign. There is a rapid reentry circuit within the AV node resulting in simultaneous atrial and ventricular depolarisation. The P-wave is usually buried within the QRS or ST-segment. There will be fast regular narrow complex tachycardia, and P-waves can be seen buried in the terminal portion of the QRS complex which may easily be mistaken for a second, small R-wave. The very close proximity of the QRS and P-waves implies near simultaneous depolarisation of atria and ventricles.

ATRIO VENTRICULAR REENTRY TACHYCARDIA (AVRT)

This occurs in patients with WPW, and is usually benign unless there is coexisting structural heart disease. There is an accessory pathway bridging the atria and ventricles allowing antegrade conduction down the AV node (causing a narrow QRS) and retrograde conduction back to the atria via the accessory pathway. Since the depolarisation wave takes time to complete this circuit, the P-wave occurs after the QRS complex and is often buried within the T-wave. AVRT can occur with antegrade conduction to the ventricles via the accessory pathway, but this will result in ventricular depolarisation via an abnormal route and consequently a broad QRS. In sinus rhythm, antegrade conduction via the accessory pathway produces a short PR interval (as the normal delay in the AV node is avoided) and the abnormal activation of the ventricles produces a slurred upstroke

in the QRS called a delta wave. The QRS complex is said to be pre-excited and can be associated with repolarisation abnormalities. There are seven sinus beats followed by a ventricular ectopic beat that conducts to the atria retrogradely through the atrioventricular node and then returns to the ventricles via the accessory pathway. This cycle repeats and triggers a broad complex tachycardia. (Please see post on ‘WPW Syndrome’ also).

An unstable patient presenting with a regular narrow complex tachycardia should be treated with electrical cardioversion. If this is not immediately available, adenosine should be given as a first-line treatment. A stable patient presenting with a regular narrow complex tachycardia should initially be treated by vagal

manoeuvres such as carotid sinus massage or the Valsalva manoeuvre, as these will terminate up to a quarter of episodes of PSVT. Carotid sinus massage should be avoided

in the elderly, especially if a carotid bruit is present, as it may dislodge an atheromatous plaque and cause a stroke

Management

A stable patient presenting with a regular narrow complex tachycardia should initially be treated by vagal manoeuvres such as carotid sinus massage or the Valsalva manoeuvre, as these will terminate most episodes of PSVT. Carotid sinus massage should be avoided in the elderly, especially if a carotid bruit is present, as it may dislodge an atheromatous plaque and cause a stroke. If the tachycardia persists and is not atrial flutter, 6 mg of adenosine should be given as an IV bolus, followed by a 12 mg bolus if no response. A further 12 mg bolus of adenosine may be given if the tachycardia persists. Vagal manoeuvres or adenosine will terminate almost all AVNRTs or AVRTs within seconds, and therefore failure to convert suggests an atrial tachycardia such as atrial flutter. If adenosine is contraindicated, or fails to terminate a narrow complex tachycardia, without first demonstrating it as atrial flutter, give a calcium-channel blocker, e.g. verapamil 2.5–5 mg IV over two minutes. Atrial flutter should be treated by rate control with a beta-blocker.

An irregular narrow complex tachycardia is most likely to be atrial fibrillation (AF) with an uncontrolled ventricular response, but may also be atrial flutter with variable block. If the patient is unstable, synchronised electrical cardioversion should be used to treat the arrhythmia

Atrial fibrillation(AF) is a supra-ventricular arrhythmia characterized by the complete absence of co-ordinated atrial contractions. There will not be any discernable p-waves.

The ventricular response rate depends on the conduction of the AV node.

WHAT IS THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN ATRIAL FIBRILLATION AND ATRIAL FLUTTER

Flutter is a more organised and regular form of atrial activity and classically with an atrial rate of 300 bpm. ‘Saw toothed’ flutter waves are present on the ECG. The ventricular response depends on conduction through the AV node. The classic ECG has 2:1 block, hence a ventricular rate of 150 bpm

CAUSES OF AF IN THE PERIOPERATIVE SETTING

Electrolyte abnormalities especially low potassium or magnesium

Withdrawal of beta blockers

Following cardiac surgery.

ASD or mitral valve disease

Ischaemic heart disease

Thyrotoxicosis

Excess caffeine or alcohol (acute or chronic)

Pulmonary embolism

Pneumonia

Pericarditis

In the context of major vascular surgery, systemic inflammation,hypovolemia and a heightened adrenergic state are likely to play a major role.

WHAT IS LONE AF?

‘Lone AF’ is AF in the absence of any demonstrable medical cause, but this is not usually diagnosed in the peri-operative period. So beta blockers will be efficacious in this setting.

WHAT ARE THE PROBLEMS AF CAN POSE?

Loss of the atrial ‘kick’ as it contracts and empties into the LV can reduce the CO by 10%–20% with a normal ventricle (reduced by 40%–50% in those with a ‘stiff’ ventricle as in

diastolic dysfunction, aortic stenosis etc). The disorganised contractions of the atria cause stasis of blood and the risk of thromboembolism. There is a 3%–7% annual risk of

thromboembolic CVA

AF- EVALUATION

*History *Assessment of volume status and electrolytes *ECG: This will also help to exclude acute ischaemia. *The pulse will be irregularly irregular. *No ‘a wave’ in the jugular venous pulsation as this is caused by sinus atrial contraction. *Chaotic atrial activity can be seen on echocardiography.

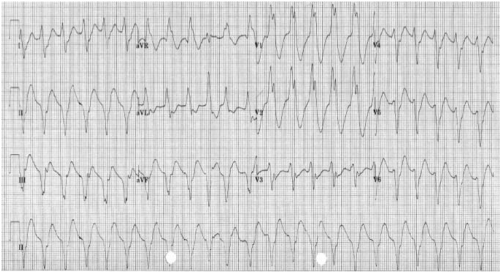

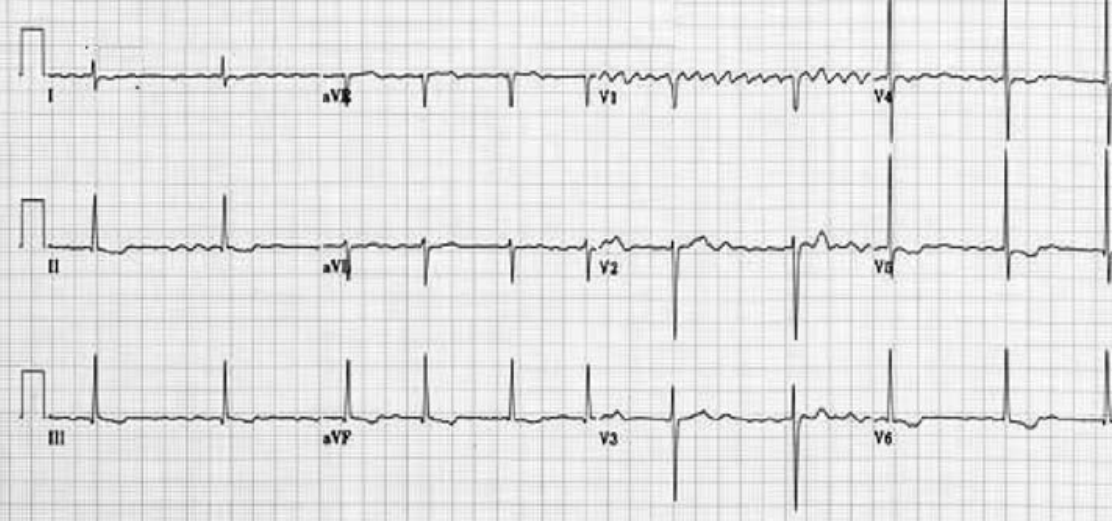

READ THIS ECG

MNEMONIC ‘RIAS QRST’ (Rate & Rhythm, Intervals, Axis, QRS & ST segment T wave)

The rate is 78 bpm; the rhythm is irregularly irregular. There are flutter waves seen in the V1 rhythm strip. The axis is normal (There is borderline LVH by voltage criteria). There are no Q waves and the QRS width is normal. There is evidence of infero-lateral ischaemia shown by the inverted and biphasic T waves in this territory (II, III, aVF and V3−V6).

MANAGEMENT OF AF

Assess for cardiovascular compromise and resuscitate simultaneously if needed. Oxygen should be administered, continuous ECG monitoring instituted and IV access secured.

If the patient is unstable, synchronised electrical cardioversion should be used to treat the arrhythmia.

In a stable patient, treatment options include: Rate control by drug therapy. Drugs used to control the heart rate include beta-blockers, digoxin, magnesium, the non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (verapamil or diltiazem) or a combination of these.

Rhythm control by amiodarone to encourage cardioversion: Amiodarone is given as a 300 mg IV bolus, followed by 900 mg IV over 24 hours.

Rhythm control by electrical cardioversion: This is more likely to restore sinus rhythm than chemical cardioversion.

Treatment to prevent complications. Patients who are in AF are at risk of atrial thrombus formation and should be anticoagulated

Patients who have pre excitation syndromes with an accessory conduction pathway between the atria and ventricles (such as in the Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome) should not be given AV node blocking drugs if they develop an SVT. This will promote the atrial impulses to travel directly to the ventricle at up to 300 bpm via the accessory pathway. The drugs of choice are amiodarone, flecainide or procainamide.

BEFORE PROCEEDING WITH DC CARDIOVERSION FOR AF, WHAT ALL THINGS SHOULD BE CONSIDERED?

ANESTHESIA FOR CARDIOVERSION

This should be done in a critical care or operating room area with the usual preparation, equipment and assistance needed for any routine anaesthetic. Someone independent should be present to perform the defibrillation, preferably with a hands-free device. Elective cardioversion has been done under conscious sedation without any adverse effects, but the usual technique is to use a sleep dose of propofol following pre oxygenation. One can use a facemask or maintain the airway with an LMA. If there is any serious doubt about cardiovascular performance or reserve, an arterial line should be given consideration, but this is a short procedure and the cardiac output should improve with the restoration of sinus rhythm. If the patient has a pacemaker in situ or an implantable cardiac defibrillator, we should place the paddles as far away as possible from the device and preferably in the anterior–posterior position.

IF THE PATIENT DOES NOT GET CARDIOVERTED, WHAT SHOULD YOU DO?

Try a period of 4–6 weeks of medical therapy and anticoagulation. If the patient is still in AF, then a further trial of DCC is reasonable. If a second DCC is unsuccessful, then rate control is the next step to improve symptoms and reduce ventricular failure.