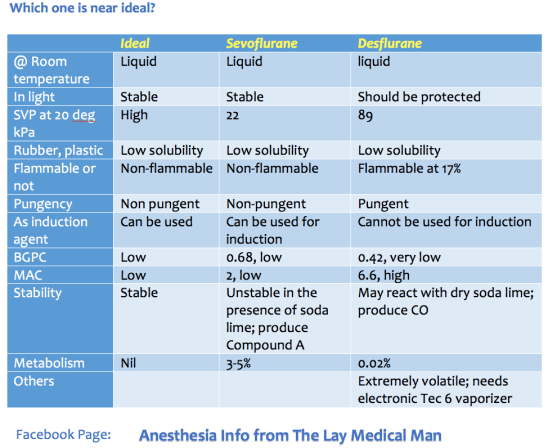

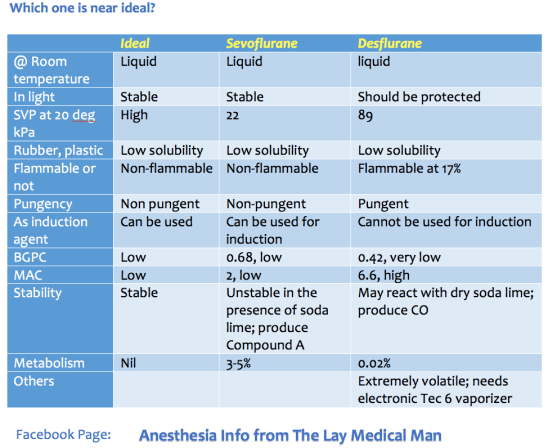

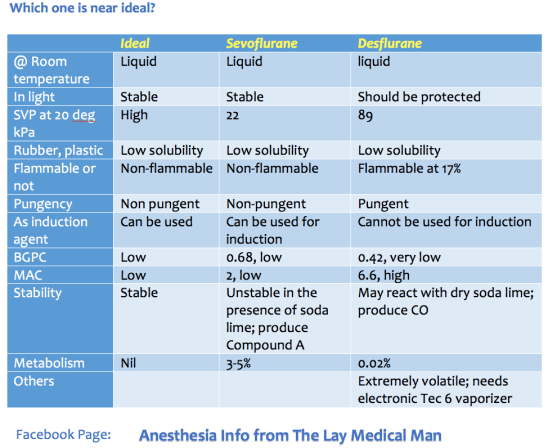

VIVA SCENE: Ideal Inhalational Agent

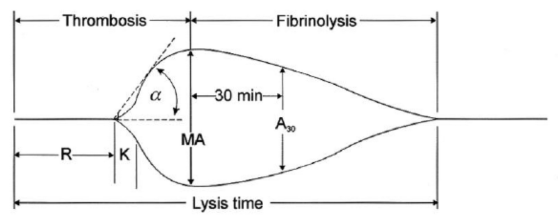

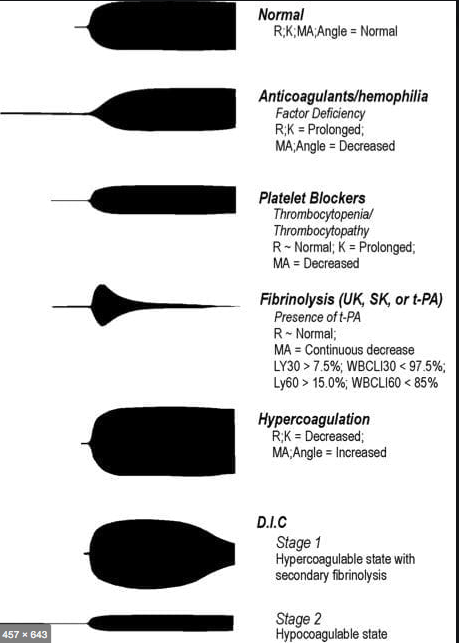

TEG is a relatively new modality for monitoring coagulation which is very useful during management of trauma and also in the perioperative scenario..

BASIS:

INTERPRETATION

R(sec): The first measurement of note is the reaction time (R time). This is the time interval from the start of the test to the initial detection of the clot. Normal R values range between 7.5 and 15 minutes. A prolonged R time may indicate hemodilution or clotting factor deficiencies. The treatment for prolonged R time is to administer FFP as it contains all factors of the coagulation cascade, without further coagulant hemodilution. A shortening of R time (< 3 minutes) occurs in hypercoagulable states. Examples would be patients with early disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) or septicemia. In these situations, free thrombin is released into the circulating blood, triggering the clotting mechanisms but the patient later begins to bleed because of exhaustion of clotting factors.

K (sec) and Angle α (°): The clot strength is measured by these 2 variables in TEG. The K value measures the interval between the R time and the time when the clot reaches 20 mm. Normal K values range between 3 and 6 minutes. Prolongation of the K value with normal platelet count indicates inadequate amounts of fibrinogen to form fibrin. The treatment for prolonged K value is therefore to administer fibrinogen/cryoprecipitate. The α angle measures a line tangent to the slope of the curve during clot formation.The alpha angle represents the thrombin burst and conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin. Normal α value is between 45° and 55°. A longer K value causes a shallow or more acute angle (<45°), while a shorter K value causes a steeper α angle (>45 °). An angle α <45° suggests a less vigorous association of fibrin with platelets. In this case, treatment begins much higher on the coagulation cascade, with the replacement of both fibrinogen and factor VIII. Thus, these patients can be treated with the administration of cryoprecipitate. Shortening of the K-value indicates a very quick formation of clot, potentially due to hypercoagulability or inappropriate consumption of coagulation factors. A shortened K value also corresponds to a steeper α (>45°). The treatment for shortened K and steeper α is anticoagulation therapy

Ref: Thromboelastography: Clinical Application, Interpretation, and Transfusion Management, Shawn Collins et al AANA Journal Course, 2016

HOW DO WE TEST CLOTTING?

Normal value is 3 to 10 minutes.

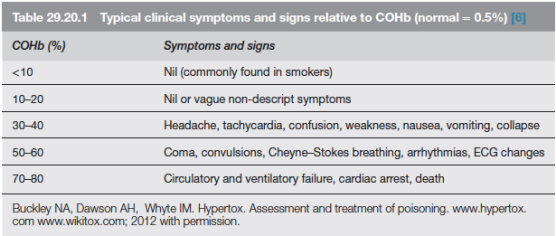

AETIOLOGY: Carbon monoxide is produced by incomplete combustion and is found in car exhaust, faulty heaters, fires and in industrial settings. Carboxyhaemoglobin (COHb) concentrations in cigarette smokers range as high as 10%.

MECHANISM: Binds to Hb with 210 times affinity than O2: so reduce the O2 carrying capacity of blood. Also disrupts oxidative metabolism, binds to myoglobin and cytochrome oxidases, causes lipid peroxidation. Final result is tissue hypoxia. Severity depends on the duration of exposure, CO levels and patients pre-event health status: pre-existing cerebral disease, cardiac failure, hypovolemia and anemia increase toxicity

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS: Cyanide poisoning ( suspected when CNS effects are out of proportion with COHb concentrations and if there is a marked lactic acidosis)

EVALUATION & MANAGEMENT:

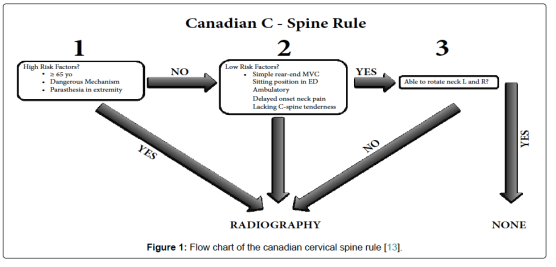

WHETHER TO DO C SPINE IMAGING IN TBI; CRITERIAS:

1.

2. Under the NEXUS guidelines, when an acute blunt force injury is present, a cervical spine is deemed to not need radiological imaging if all the following criteria are met:

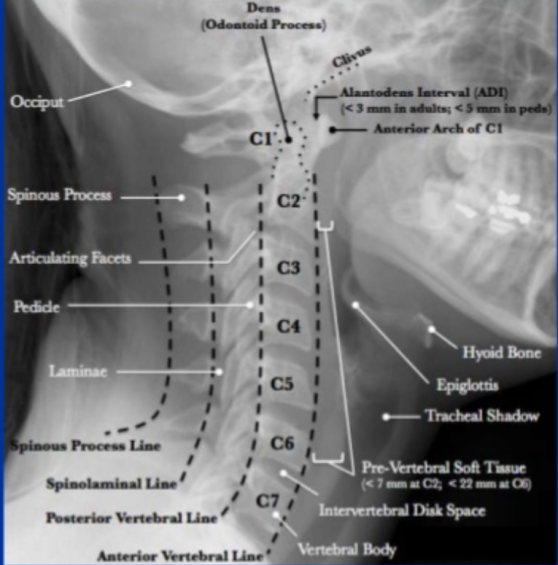

Lateral C-Spine Radiograph. (AABCDs)

A—Adequacy: An adequate film should include all seven cervical vertebrae and C7/T1 junction with optimum density so that the soft tissue shadow is visible clearly.

A—Alignment

a. Atlanto occipital alignment: The anterior and posterior margins of the foramen magnum should line up with the dens and the C1 spinolaminar line.

b. Vertebral alignment

Look for the following four lines (any incongruity= should be considered as evidence of ligamentous injury or occult fracture)

1. Anterior vertebral line—joining the anterior margin of vertebral bodies

2. Posterior vertebral line—joining the posterior margin of vertebral bodies

3. Spinolaminar line—joining the posterior margin of spinal canal

4. Spinous process/ Interspinous line—joining the tips of the spinous processes

B Bony Landmark: vertebral bodies, pedicles, laminae, and the facet joints are inspected

C Cartilagenous space: Predental space or the Atlanto-Dental Interval (ADI): which is the distance from dens to the body of C1. ADI should be < 3 mm in adults and < 5 mm in children. An increase in ADI depicts a fracture of the odontoid process or disruption of the transverse ligament

D—Disc space

Disc spaces should be roughly equal in height and symmetrical.

Loss of disc height can happen in degenerative diseases.

S—soft tissue

Prevertebral soft tissue space thickness can help in the diagnosis of retropharyngeal haemorrhage, which can be secondary to vertebral fractures. Maximum allowable distances :

Nasopharyngeal space (C1): 10 mm

Retropharyngeal space (C2–C4): 5–7 mm

Retrotracheal space (C5–C7): 14 mm in children and 22 mm in adults

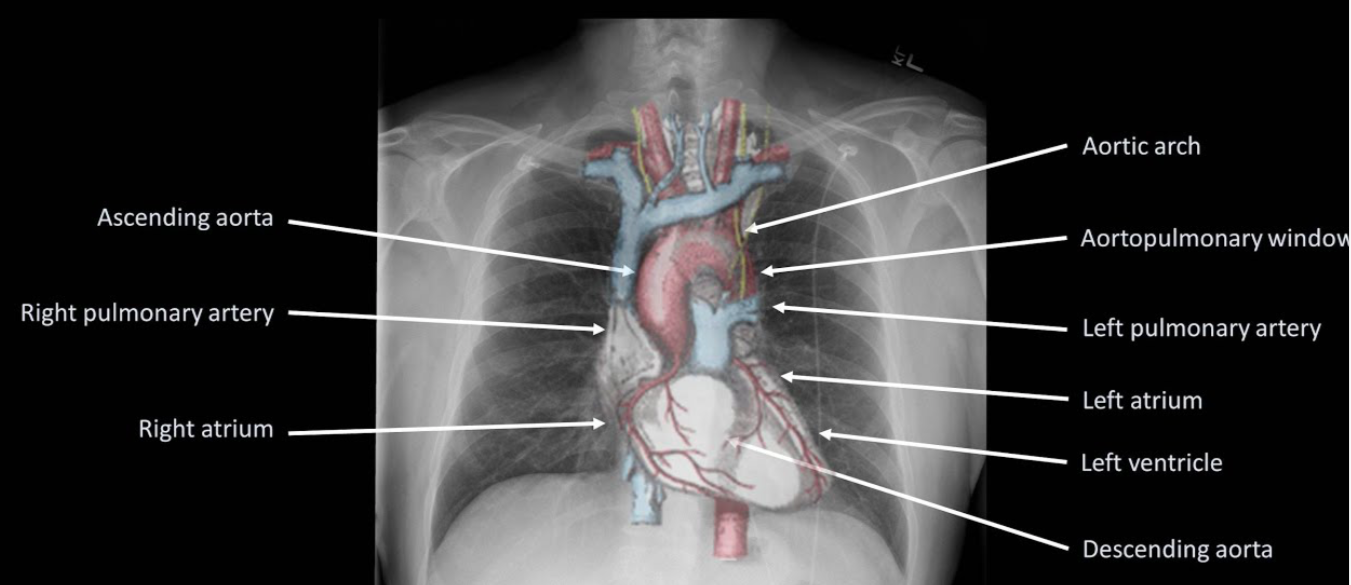

CVS:

AIRWAY/ RESPIRATORY SYSTEM

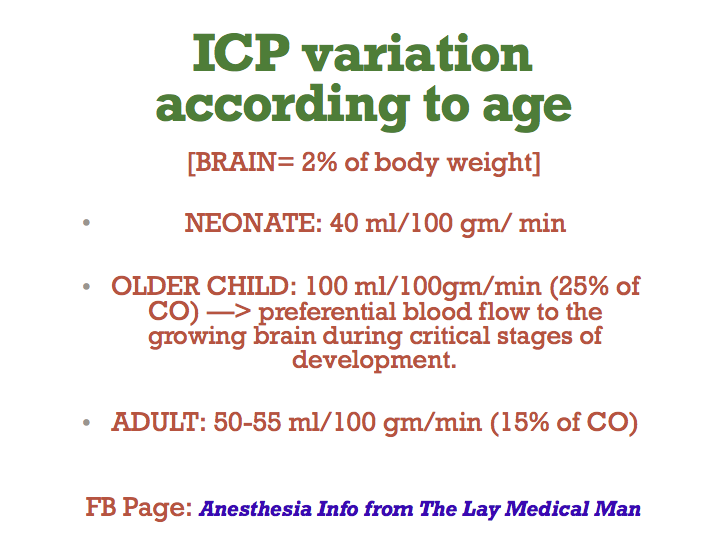

CNS

TEMPERATURE REGULATION

Higher thermoneutral temperature (temperature below which an individual is unable to maintain core body temperature) 32 degree C for a term infant compared with 28 for an adult.

RENAL SYSTEM

HEPATIC SYSTEM

Low hepatic glycogen stores means hypoglycaemia occurs readily with prolonged fasting

DRUG ADMINISTRATION

MAC is age related. MAC values for an infant are: • sevoflurane = 3.3% • isoflurane = 1.9% • desflurane = 9.4%.

1. PYLORIC STENOSIS (PROTOTYPE CASE; ANY OTHER CASE, MAKE THIS A TEMPLATE AND ADD SPECIFIC POINTS RELEVANT FOR THAT CONDITION)

Most common cause of intestinal obstruction in infancy

Due to hypertrophy of circular pyloric muscle

Presentation: 4-6 weeks of age

Persistent projectile vomiting

There is obstruction at the level of pylorus: so bicarbonate rich fluid from intestine cannot mix with gastric secretions

So the vomiting causes metabolic alkalosis and hypokalemia due to loss of acidic gastric juice alone

The large bicarbonate load is in excess of kidney’s absorptive capacity and the urine becomes alkaline initially

Later when the fluid and electrolyte loss result in dehydration, the renin angiotensin system is activated and result in aldosterone secretion which tries to preserve sodium at the expense of K and Cl ions

This result in production of paradoxical acidic urine and worsening of metabolic alkalosis and hypokalemia

An attempt to compensate it through hypoventilation is initiated; but it will be insufficient and also this will trigger the hypoxic drive!

Hypoglycemia, hemoconcentration, mild uremia and unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia may be seen.

ANAESTHETIC CONCERNS

Pyloric stenosis is not an emergency

The DYSELECTROLYTEMIA and ACID BASE IMBALANCE should be corrected before taking up for surgery.

Increased chance for regurgitation, altered physiology and anatomy, altered drug dosages, difficult venous access, anxious parents are other concerns

There should be an experienced paediatric anaesthesiologist for the conduct of anaesthesia

P.A.C. AND EVALUATION

LOCATION: Needs resuscitation in a paediatric ICU or ward

INVESTIGATIONS: CBC, Blood sugar, RFT, LFT, group and hold, serial ABGs to know the effectiveness of resuscitation and decide on the dose of K administration. 3 mmol/kg/24 hour potassium should be added to maintenance fluids

HISTORY: From the parent; vomiting frequency, amount of feeds taken, diarrhoea, frequency of wetting of the nappy, fever, altered sensorium

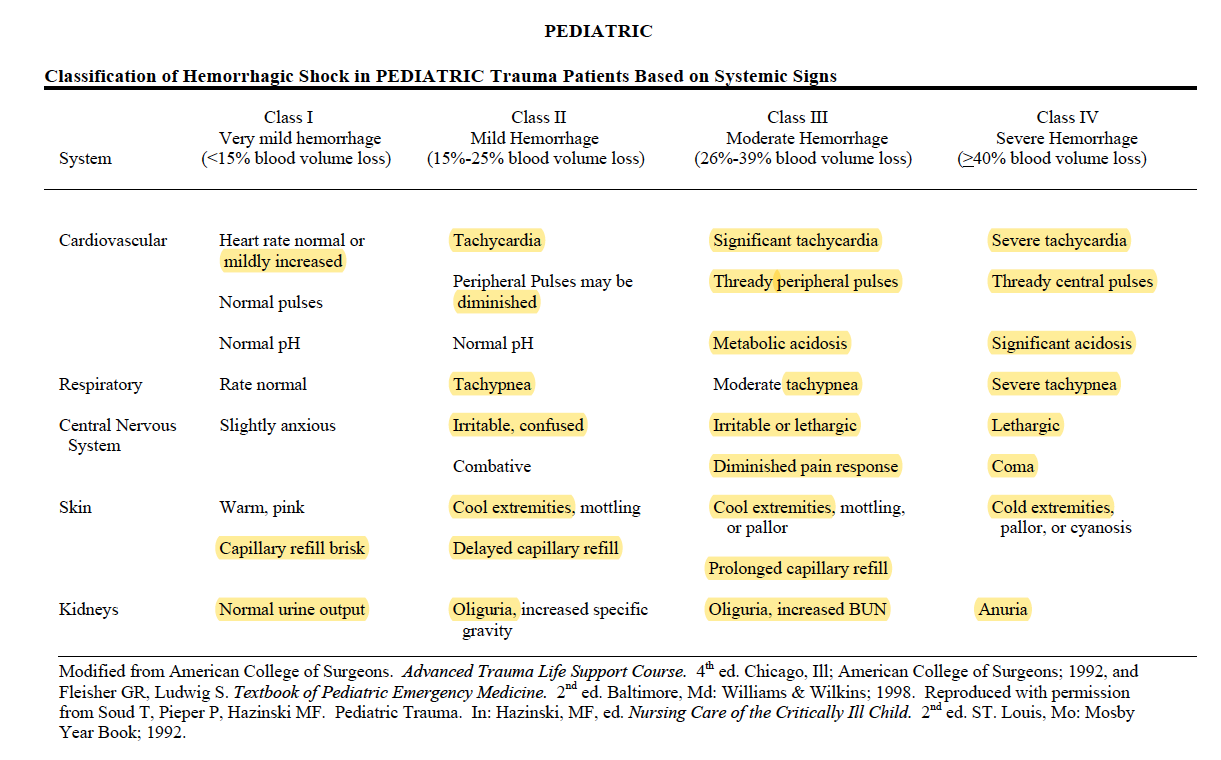

EXAM: ?Dry mucus membrane ?Dry eyes (5% dehydration) ?Sunken fontanelle ?cool peripheries ?oliguria(10%) ?Hypotension ?Tachycardia ?Altered Sensorium (10%) ?prolonged capillary refill time

Naso Gastric tube insertion and 4 hourly aspiration of residue

FLUID RESUSCITATION:

MAINTENANCE FLUIDS:

TARGETS:

CONDUCT OF ANAESTHESIA

OTHER INTRAOPERATIVE CONCERNS

PAIN EVALUATION IN PAEDIATRICS

POSTOPERATIVE CARE

2.INTUSSUSCEPTION

3.OESOPHAGEAL ATRESIA (OA) & TRACHEO OESOPHAGEAL FISTULA (TOF)

4.CONGENITAL DIAPHRAGMATIC HERNIA (CDH)

5.EXOMPHALOS & GASTROSCHISIS

6. INGUINAL HERNIA / REGIONAL TECHNIQUES

Mask or IV induction with general anesthesia (with or without endotracheal intubation); spinal anesthesia as a primary anesthetic; caudal anesthesia or analgesia. Muscle relaxation is not necessary but may be a valuable adjunct for decreasing anesthetic requirements and providing optimal surgical conditions.

Equipment: Low compression volume anesthesia breathing circuit (circle absorption system vs. Mapleson D ). Monitoring: Standard noninvasive monitoring

Emergence and Perioperative Care: 1. Vigilance regarding perioperative abnormalities of control of breathing: periodic breathing/apnea; laryngospasm/bronchospasm; bradycardia; hypoglycemia; continuously monitor with a pulseoximeter. 2. Pain management. (See:1)

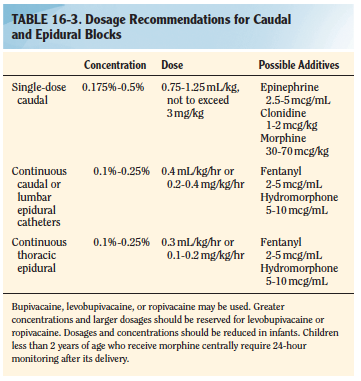

Regional anaesthesia:

TBI MANAGEMENT (Based on BTF 4e Guidelines)

Lidocaine in doses of 1.5 mg/kg may inhibit the adverse effects of laryngoscopy decreasing ICP, CMR, and CBF with minimal hemodynamic effects

Propofol may be used for ICP control. High dose barbiturates are recommended to control ICP refractory to maximum standard surgical and medical treatments while ensuring hemodynamic stability

Drain CSF for the first 12 hours for patients with a GCS of less than 6. Continuous drainage is better than intermittent

ICP Monitoring is Indicated if GCS is 3-8 and an abnormal CT OR Indicated if GCS is 3-8, there is a normal CT, and any two of the following

Decompressive craniectomy has been used but has not been found to improve outcome

Treatment with anticonvulsants within 7 days of injury

Glucose-containing fluids should be avoided and blood sugar monitored to maintain levels between 4–8 mmol/L.

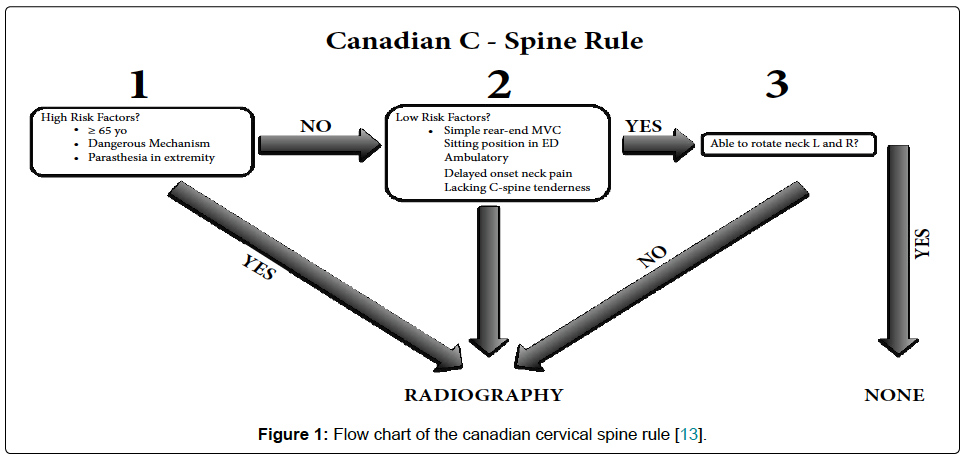

SHALL WE DO A C-SPINE IMAGING?

2. CANADIAN C-SPINE RULE

MANAGEMENT OF SDH: SPECIFIC POINTS

Subdural hematomas are the most common focal intracranial lesion

They have the highest mortality rate of all lesions , which is likely due to the associated brain injury and decrease in cerebral blood flow that accompany these lesions. Outcome worsens as the amount of midline shift exceeds the thickness of the hematoma

The hematoma is located between the brain and the dura and has a crescent shape. It is usually caused by tearing of the bridging veins connecting the cerebral cortex and dural sinuses

The management of these lesions is immediate surgical decompression, which has been shown to improve outcome

MANAGEMENT OF EDH: SPECIFIC POINTS

They generally have a better prognosis than subdural hematomas with the main determinant of outcome being preoperative neurologic status

Epidural hematomas are biconvex and are located between the dura and skull

The usual etiology is a torn middle meningeal artery, but the blood may also come from a skull fracture or bridging veins.

The classic presentation includes a lucid interval followed by neurologic deterioration and coma

Treatment is prompt surgical decompression when the following criteria are met: more than 30 mL for supratentorial and more than 10 mL for infratentorial hematomas, thickness of more than 15 mm, midline shift of more than 5 mm, or the presence of other intracranial lesions

Expectant management with close observation is acceptable for small lesions.

Since the brain parenchyma is usually not injured, the prognosis is excellent if the hematoma is rapidly decompressed